The following is a revised and expanded version of a segment that originally appeared in a post from my other Substack. I have reworked it as an entry to the series.

There was once a king who always wore a large cap over his head — large enough to cover his ears. He wore it when he ate, when he bathe, and even when he slept. Nobody knew why he covered his head, and the king would always avoid answering the question whenever asked.

Only the barber — who had to cut the king’s hair — knew the answer, but that was no help either. For each time the king had a haircut, a new barber would be summoned to the palace. And once the task was done, the unfortunate soul would be thrown into the dungeon. Before long, there were fewer and fewer barbers left in the realm — and more and more prisoners filling the royal dungeon.

As you can imagine, the king was not very popular. The people of the realm began to whisper to each other in secret, wondering what the king was so desperate to hide.

“Perhaps the king is bald.”

“Perhaps he has an ugly hole in his head.”

“I, for one, think he has horns like the devil himself.”

But no one dared to speak badly of him in public, lest they should be punished like the barbers.

Not far from the king’s palace lived an old barber. He would have retired by now, had he not taken on an apprentice named Collin, a young man just beginning his trade. Collin was soft-spoken and shy, but he had steady, nimble hands, and a natural talent for his craft.

Some well-meaning folk asked him why he had chosen to become a barber, knowing what fate awaited those in his profession. To this, Collin simply said, “It’s what I do best. Besides, I need to earn a living somehow. My widowed mother is sick and bedridden, and I’m all she’s got.”

Sooner than expected, Collin was summoned to cut the king’s hair. He felt rather nervous as he stepped into the palace, for he knew all too well that every barber before him had entered and never returned. “What will become of me?” he wondered.

Collin was led to the king’s chamber, where the ruler sat before a large mirror. The door shut behind them. The lock turned.

“Well, I haven’t got all day. Get to work!” the king commanded.

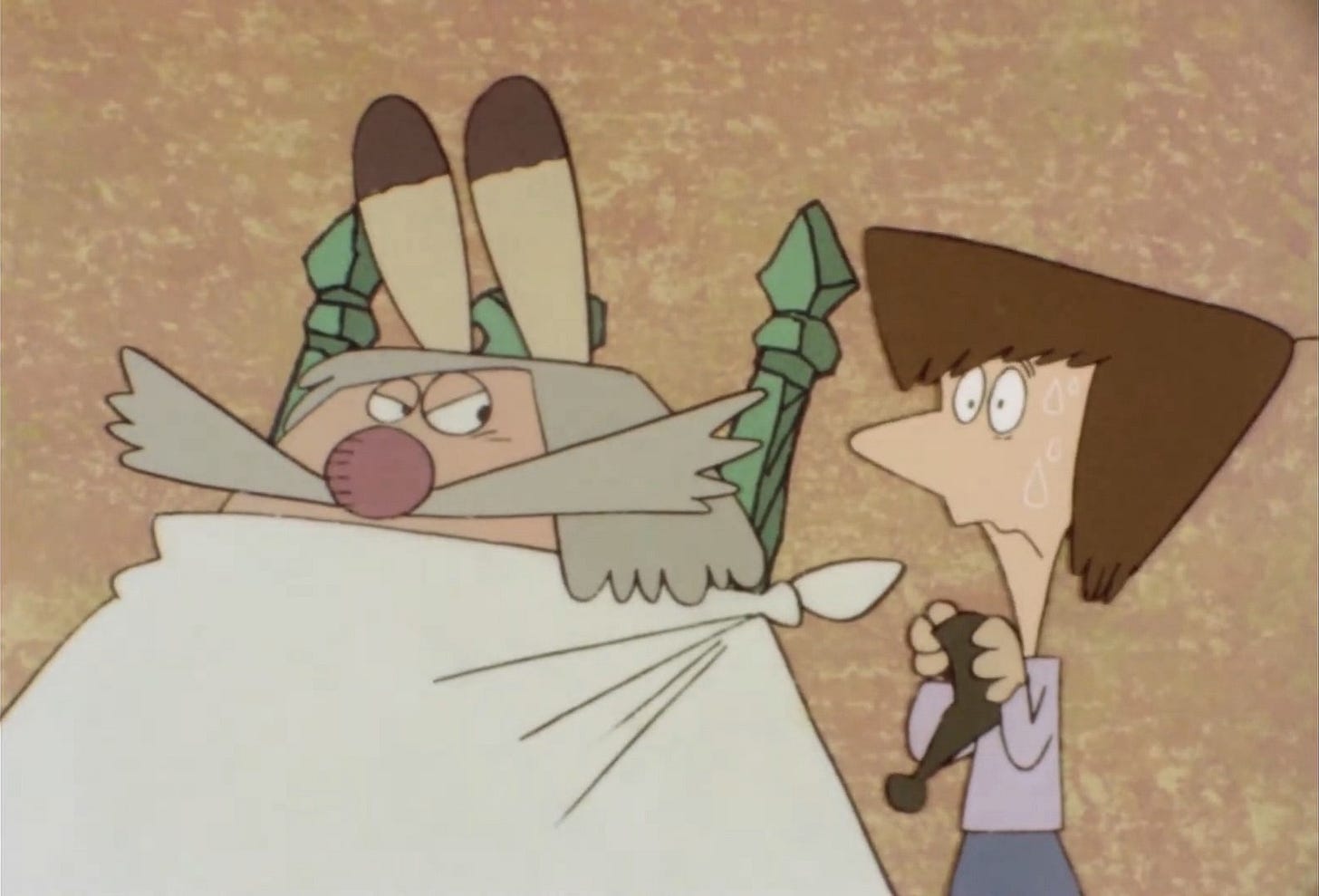

So Collin got his comb and scissors and set to work, all while trembling with fear. His fear turned to shock when he removed the king’s cap — and saw a pair of long, furry donkey’s ears popping up!

Collin gasped but said nothing. He proceeded to cut the king’s hair, neither of them saying a word. But as soon as the task was done, the king said, “Alright, to the dungeon with you! No one can ever know about my ears. I’d be the laughing stock of the entire realm, and I cannot afford that.”

“But my mother is sick at home,” Collin pleaded. “And I’m the only one she’s got. Please let me go. I’ll never tell anyone about… you know what.”

Well, the king thought about it. Whether it was out of pity or just a matter of administration (between you and me, the dungeons were nearly full, and there were no barbers left in the realm), the king agreed to let the barber go. “But if you tell a single person about… you know what… you shall be accordingly punished.” And he drew his finger across his throat.

The terrified barber just gulped and nodded.

Everyone was surprised to see Collin back at his shop, but when asked about his encounter with the king, he remained tight-lipped. All he said was that the king must have had a change of heart to let him go.

So life went on as usual, except now Collin had a great secret to keep. And as the days passed, it weighed on him more and more. He couldn’t sleep. He could barely eat. His hands shook when he had to cut hair. All day and all night, the same words rang in his head, over and over: The king has donkey’s ears! The king has donkey’s ears!

Collin longed to share his secret with someone — anyone! — but he knew that if he did, he would be killed. At last, he had an idea. The king had made him promise not to tell the secret to anyone. But he didn’t say not to anything.

Collin ran deep into the forest, where no one — no person, no animal, no bird — could hear him. He found a large tree, pressed his lips against the hollow of its trunk, and shouted at least twenty times: “The king has donkey’s ears! The king has donkey’s ears!”

Then he heaved a sigh of relief and went back home. “I feel much better already,“ he thought. And he did.

But life has a funny way of coming back at you, when you least expect it.

A few weeks later, the king planned a grand feast to celebrate the harvest season. In honour of this occasion, a famous harpist was to perform and sing before the entire realm. But one week before the day of the feast, the harpist found a crack in the pillar of his harp. So he went into the forest to find wood to repair it. And the tree he cut the wood from was the very same one Collin had told his secret to!

One week later, the harp was fixed and ready to be played. The whole realm gathered to see the harpist perform. But as he plucked at the strings, a strange sound came out of it: “The king has donkey’s ears! The king has donkey’s ears!”

Thus the whole realm now knew the king’s secret. And the king was livid.

“Throw the harper into the dungeon!” he bellowed.

“But Your Majesty,” the harpist stammered, “it’s not my fault. It’s the harp! It must be bewitched.”

To prove his point, he plucked the strings once more, and once more the harp sang: “The king has donkeys ears! The king has donkey’s ears!”

The crowd gasped. The king’s face turned red with rage.

“Guards! Bring the barber Collin to me!” he commanded.

The guards quickly spotted Collin cowering among the crowd. He tried to flee, but they seized him and dragged him before the king.

“I told no one, Your Majesty, I swear it,” Collin pleaded.

“You were the only one who knew,” the king growled. “That means you must have revealed it to someone.”

And so, with no other choice, Collin confessed how he had whispered the secret into the tree. “I couldn’t keep it inside,” he admitted. “It weighted too heavily on me. And besides, it was the truth — you do have donkey’s ears.”

“Enough!” roared the king. “Guards! Take Collin and the harpist to the executioner!”

But before the guards could move, the people erupted in protest. They booed and jeered at the king’s cruel order. Some even surged forward, trying to stop the guards, but they were quickly overpowered. And then, one by one, they all removed their hats and caps, and chanted:

“We all have things to hide! Why should the king be any different?”

The king looked at the sea of bare heads before him, at his subjects — his people — who no longer feared him. If he went through with the execution, they might rise against him, and that would never do. Remember, the king cared very much about what others thought of him. Why else would he have hidden his ears in the first place? And he certainly didn’t want to lose his throne.

At last, he took a deep breath and raised a hand.

“Stop!” he said to his guards. “Let the barber and the harpist go.”

A hush fell over the crowd.

Then the king turned to his people and, with a heavy sigh, removed his crown and cap. Two long, furry donkey’s ears popped out.

For a moment, there was silence. Then the crowd erupted — not in outrage, but in laughter, cheers, and applause. Some laughed in mockery, but most in relief.

From that day on, the realm was a much more peaceful place. The barbers were released from the dungeon. Collin became a great barber, renowned for his honesty and skill.

As for the king, he was never again ashamed of his donkey’s ears. Now, some say he became a kinder ruler. Others say he only pretended to be kind, so afraid was he of losing his throne. Whatever the case, the people of the realm finally had something to talk about without fear of persecution. And since then, the king became known as King Donkey Ears, which was just as well.

Author’s Note

When I was young, I always thought the story of “King Donkey Ears” was exclusively of Irish origin, and that it was about a king with donkey’s ears. But as is the way with folk tales, there are several variations of this ever-changing story.

Its origins come, in fact, from Greek mythology. King Midas (the one with the golden touch) worships the god Pan, and even declares his music better than Apollo’s. Enraged, Apollo curses Midas to have the ears of a donkey. Midas hides his ears by wearing a headdress and orders his hairdresser to keep the secret. Unable to keep it, however, the hairdresser whispers it to a hole in the ground. A bed of reeds grow from the hole, and at the breeze of the wind it whispers the king’s secret.

Variations of this story can be found across Europe (especially in the British Isles) and Asia. The key difference among all of them is in the kind of ears attributed to the king; they can be the ears of a horse, a goat, an ox, and, in a Filipino version, a pair of horns.

My retelling is loosely based an Irish variant of the story, “The King with the Horse’s Ears,” from Patrick Kennedy’s Legendary Fictions of the Irish Celts. I have swapped the horse’s ears with those of a donkey because the latter is more recognisable, but also for effect: donkey’s ears are much larger, and therefore much more noticeable, after all!

Most modern versions have adapted the story to be one of acceptance, by having the king learn to love his ears as they are. Lovely and necessary though the message is, I have always been bothered by how it seemingly ignores the fact that the king has punished many innocent people to keep his secret. Most traditional versions have him kill the barbers, while modern renditions have him either imprison them or make his personal barber swear to secrecy. I thought I could address this aspect in my retelling, while simultaneously use it as a commentary on what one is restricted to say in public, especially in regards to open dissent.

Bibliography

Source Material and Variants

Bompas, Cecil Henry. “The Child with the Ears of an Ox.” Folklore of the Santal Parganas. David Nutt, 1909.

Bulfinch, Thomas. “Midas—Baucis and Philemon.” Bulfinch’s Mythology: The Age of Fable; The Age of Chivalry; Legends of Charlemagne. Grosset & Dunlap, 1913.

Burns, Batt. “The King with Horse’s Ears.” The King with Horse’s Ears and Other Irish Folktales. Sterling Publishing Co., Inc., 2009.

Cole, Mabel Cook. “The Presidente Who Had Horns.” Philippine Folk Tales. A. C. McClurg and Company, 1916.

Kennedy, Patrick. “The King with the Horse’s Ears.” Legendary Fictions of the Irish Celts. Macmillan and Co., 1866.

Lang, Andrew, editor. “The Goat’s Ears of the Emperor Trojan.” The Violet Fairy Book. Longmans, Green, and Co., 1901.

Thomas, W. Jenkyn. “King March.” The Welsh Fairy Book. T. Fisher Unwin, Ltd., 1908.

Retellings and Adaptations

Donaldson, Julia. “The King’s Ears.” A Twist of Tales. 2000. Barrington Stoke Ltd., 2016

Harvey, Damian. The King with Horse’s Ears. Franklin Watts, 2020.

“The King’s Ears.” Tales of Magic (Manga Sekai Mukashibanashi), Dax International, 1976.

“King March: A Story from Wales.” Animated Tales of the World, directed by Jiri Latal, Studio Jiřího Trnky, 2002.

“The King with Donkey’s Ears.” Classic Tales, directed by Craig Handley, Southern Star Entertainment Pty Ltd., Colorland Animation Productions and Neptuno Films, 2008.

Maddern, Eric. The King with Horse’s Ears. Frances Lincoln, 2004.

McCaughrean, Geraldine. “King Midas.” The Orchard Book of Greek Myths. Orchard Books, 1992.

Sims, Lesley. “King Donkey Ears.” Usborne Illustrated Stories for Bedtime. Usborne Publishing Ltd., 2010.

Thomas, Peggy. The King has Horse’s Ears. Simon & Schuster Inc., 1988.