Once, not long ago — when brides were few and suitors were many — there was a girl named Aniela. She had been good-natured and shrewd as a young girl, and she was even more so when she became a young woman. People often remarked that she was the very image of her departed mother.

Aniela’s father was a miller. He was a hard worker, grinding corn and wheat from miles about, and so his business prospered, and he became wealthy. Suitors came from far and wide to court his daughter, but she chose a man of modest bearing, neither rich nor poor. He was honest and kind and loved her for herself and not her wealth.

All seemed to be going well. Aniela would marry her one true love and live happily ever after with him.

But Fate can be cruel and unfair sometimes.

On the very day before the wedding, Aniela’s bridegroom was mending a neighbour’s roof. Somehow or other, he slipped from the roof and fell headfirst to the ground. The fall was fatal. Aniela was inconsolable.

Months passed. Tears were shed and prayers were uttered. Then one day, the miller took his daughter aside and said to her: “You’ve grieved long enough. Go and find someone else to live happily ever after with.”

“No one can replace my departed sweetheart,” Aniela said mournfully.

“I know,” said her father understandably, “but how else will you get over your loss if you don’t seek another sweetheart. I won’t be around forever, you know. I can’t let you be sad and lonely for the rest of your life.”

Aniela did not feel ready yet to pursue another sweetheart. But she knew her father meant well, so, for his sake, she followed his advice. She met plenty of suitors willing to take her hand, she listened to their woos and compliments and in turn asked each some questions about themselves. But no matter what each suitor said or looked like, they all reminded her of her one lost love. Besides, she could tell they were only after her father’s wealth, so she had no fear in rejecting them.

***

Soon it was harvest time. Everyone — rich and poor, young and old — worked all day long. Though she still carried a great sorrow in her heart, Aniela put on a brave face and took part in the work. In the evenings, the villagers would gather inside and in front of the tavern and drink and laugh and talk, while the children ran about in their games. But Aniela had no heart to join in the fun. She just sat by herself and listened to the people talk.

There was one person in particular whom Aniela liked listening to. He was a young man, cheerful and well-mannered. And very good-looking, thought Aniela.

“Name’s Aleksandr,” someone told Aniela, after seeing her stare admiringly at the man. “He’s a newcomer. Just moved in a couple days ago. He lives in the dark woods near the village. Brave fellow if you ask me. And rich to boot, too.”

Aniela could see that. Aleksandr wore a fine red suit with gold buttons and cuffs and polished boots with silver toes and tops. He even had a grand black horse hitched outside, with a bridle trimmed in gold.

There was something else Aniela noticed: that Aleksandr seemed to like her, too. Whenever he saw her looking at him, he would smile a wide, easy smile, before she, blushing, could turn away. Eventually she began to sit next to him every time she saw him at the tavern. She laughed at his easy jokes, marvelled at his careless laughter and stared into his wonderful eyes.

Days passed. Aniela continued to watch and sit next to Aleksandr, too bashful to say a word to him. Then one day, Aleksandr began to talk to her. It was sweet little nothings, really — “How are you doing?” “You did a great job in the fields today,” “You have such a beautiful smile” — but it was enough for Aniela to be completely won over by him.

Every day after that, the two began to meet and talk and laugh and overall have a wonderful time together. Sometimes Aleksandr would steal apples from the harvest barrels for her. He even helped ease her pain over her lost love. Aniela wondered why she should be so lucky as to get all of this attention from him.

Then one day, Aleksandr asked her if she wanted to be his sweetheart. “I know this may seem sudden,” he said eagerly, “but I really enjoy your company, and I know you enjoy mine too. I promise to make you the happiest woman alive.”

Aniela wasn’t sure what to say to that. Indeed it was a sudden proposal, and there was something about the way he said it that made her feel suspicious. But she did enjoy his company, and she was too polite to say no, so she consented. “But first you have to go meet my father,” she said. “He’ll be delighted to know I have a sweetheart at last.”

So, that evening, Aleksandr met with Aniela’s father. He talked in his usual charming way of this and that, admiring the miller’s house and assuring him of his reputation as the finest miller in the land. The miller was soon won over by his talk and gave his blessings to the young couple.

And yet there was something about Aleksandr — the way he talked and the way he behaved and how hard he seemed to try to please her father — that made Aniela began to hold a secret doubt about him.

Aleksandr visited Aniela (and her father) daily at the mill, and paid her (and her father) compliments each time. Within a month, the two were engaged to be married. The miller was delighted at this turn of events. Not only was the groom-to-be handsome and respected, but he had a fine house and estate, and wealth beyond measure. He would be a perfect match for his daughter.

But Aniela began to have second thoughts about her bridegroom. True, he was still charming and well-mannered, and his company was just as pleasant as ever, but sometimes she felt something was wrong about him. He had a way of looking at her which gave her a secret chill, and his laughter did not seem as easy-going as she had remembered. At last she was forced to admit to herself that she no longer trusted him. But she was too polite and afraid — both of him and her father — to say anything on the matter.

***

One day, Aleksandr said to her: “You know, my dear, we’re engaged to be married, but you’ve never paid me a visit. Why don’t you come to my house this Sunday? After all, it will soon be your home too.”

Aniela’s heart sank. “I don’t know where your house is,” she said, hoping to excuse herself.

“It’s out in the forest, at the end of the narrow road” he told her. “A beautiful place, you’ll see.”

“I still don’t know where that is,” Aniela said. “I might get lost trying to find my way through the forest.”

“No, no, you have to come. Besides, I have already invited some friends to come over, and they are eager to meet you. So that you can find the way, I’ll leave a trail of ashes to guide you.”

But Aniela insisted that she could not come, that she had too much work to do at the mill. In the end, Aleksandr smiled and told her that he understood, that it was not a problem if she could not come. But after that, for the remainder of the day, he talked to her less. When she found him at the tavern and watched him from afar, his gaze rarely turned to meet hers. By the end of the evening, he never glanced at her once — as if she no longer even existed.

Aniela felt sad and guilty. Even though she mistrusted him, she also still loved him. And really, Aleksandr had only wanted was to show her his house — her future home — and have a good time with his friends. Where was the harm in that? So just before he turned to leave, she ran and caught him by the arm. “I’ll come,” she whispered urgently. “I’ll come to your house on Sunday.”

Aleksander smiled and gave her an approving nod. “On Sunday, then,” he said, before slipping out the tavern door.

***

Sunday came and Aniela was ready to leave, but she still felt uneasy. To ease her mind, she filled her pockets with peas and beans to mark the trail in case anything happened. At the edge of the forest she found the trail of ashes, which looked like a thin, gray thread on the narrow road. Aniela followed the ashes deep into the forest. Every few steps she tossed a bean to the left and a pea to the right.

It was late in the afternoon when she reached the heart of the forest. There, hunched amidst the tall, overhanging trees, she found a large house. It was dark and silent and seemed to be deserted, but the trail of ashes led right to the front door.

“This must be my bridegroom’s house, then,” Aniela thought, shivering with fear, and knocked at the door several times. No one answered. The door was open, though, so she went in.

There was nobody inside — no bridegroom, no servants, no guests — and there was a silence all over the house. Aniela slowly walked into the parlour. It was a grand place indeed: a large chandelier was hanging from the ceiling, and cabinets filled with crystal cups, porcelain figures and gold-trimmed china were lining the walls. But the floorboards were scraped and battered, and they creaked under her every step.

Aniela was about go on, when she was startled by a shrill cry:

“Be bold, be bold, but not too bold!”

She turned around and saw that the cry was coming from a wicker basket hanging in the window. Inside a robin hopped about and flapped its wings.

“What a baffling welcome,” Aniela thought, and walked further into the house.

She went inside a bedchamber. In one corner of the room she saw some old trunks. The trunks were wide open, and they were filled with mugs and candlesticks, silver plates and gold plates, all jumbled up and in disorder. Most were stained with the hands that once held them. Some of the mugs were stained with the wine that once filled them.

In another corner of the room, there was a pile of gowns. They were evenly woven, and made from the strongest cloth, but there were rips and tears all over them. The lace was delicate and soft, but it was filled with blots, as if from tears.

As Aniela beheld this sight, the robin cried again from the cage:

“Be bold, be bold, but not too bold!”

“These objects have certainly not been taken care of properly,” Aniela thought.

She ignored the bird’s cry and entered a third room. It must have been the laundry, for there was nothing but tubs and pails in there. They were set neatly in a row, their sides painted and clean, their handles neatly carved. But as she looked closer, she saw that each cask was filled to the brim — jellied and black — with blood.

Far back in the house, the robin shrieked once again:

“Be bold, be bold, but not too bold, Lest your blood should run cold!”

“Surely it’s only horse-blood,” Aniela decided, “clotting for black pudding.”

At last she reached the entrance to a wine cellar. Descending the steep, narrow steps, she found an old blind woman sitting in dim firelight and tending a cauldron. Her head shook sadly, and her hands trembled with fear and old worries.

“I beg your pardon, good woman,” Aniela said, “but to whom do I have the pleasure of speaking?”

“I keep this unhappy place,” explained the old woman. “But what are you, with such a young, kind voice, doing here?”

“I am to marry the master of this house,” said Aniela. “Do you know where he is?”

The woman said nothing for a moment, but then she said: “Tell me, my dear, did you first meet your bridegroom at the tavern, laughing and making merry with the village folk?”

Aniela was surprised by this question, but only said: “I did.”

“And did he charm you with his sweet little nothings and his kind, polite gestures and his promises of love and happiness?”

Aniela now felt uneasy, but replied: “He did.”

“And did he ask — nay, insist — that you should come to this house, that you should visit him just as he visited you, or else he would ignore you?”

“He did,” replied Aniela, her heart beating fast. “Why do you ask?”

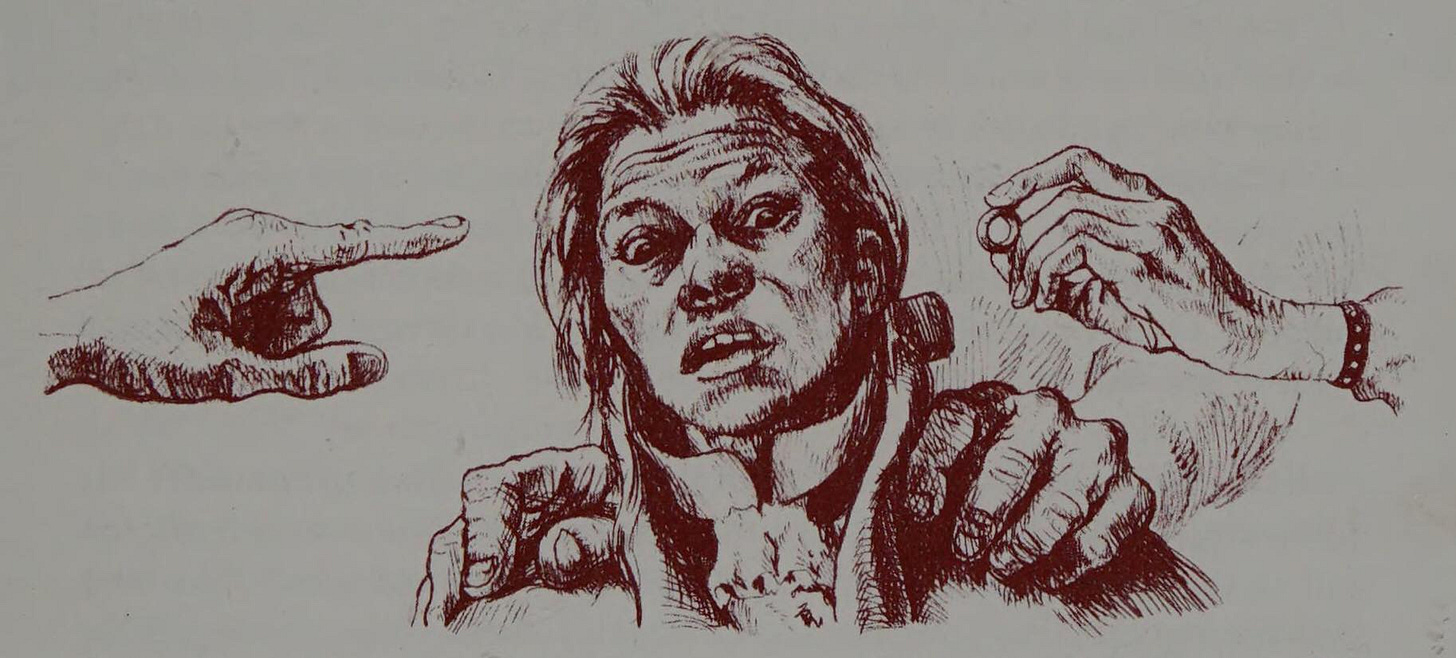

“Because, my dear, the same thing happened to me!” The old woman rose from her chair, her bones creaking and groaning. She felt her way towards Aniela and gently touched her cheek. “Poor child! You have no idea what you’ve gotten yourself into. You are in the den of a thief and a murderer!”

Aniela shook her head in disbelief. “I don’t think I understand.”

“Years ago I was brought here with a promise of marriage. Instead the villain blinded me so I could not run away, and has made me work harder than the most wretched slave. If you’re lucky, he will blind you, make you take my place, and drive me into the woods to die. But he will most likely kill you like the others.”

“Kill me!” Aniela gasped.

“Yes, yes, you heard me right. Look: I have been told to put this cauldron on to boil water. If he finds you here, he will cut you into pieces, cook you, and eat you, for he and his band — his so-called guests — are also eaters of human flesh. Where do you think he got his fine clothes and horse? From long-dead travellers!”

“Then we’ll have to flee,” urged Aniela, after recovering from her shock. “Take my hand and we’ll run away this instant!”

“There’s no use running away now,” said the old woman, shaking her head. “He and his band will return soon for their supper. I must hide you or your life is lost.”’ She took hold of Aniela’s hand. “Come, quick!”

She led Aniela to a pile of huge wine casks and hid her behind them. “Do not stir, my dear, and keep silent. If they hear you, that’s the end of you. Tonight, when the robbers are asleep, I’ll fetch you. Then we can escape together.”

Outside they heard the sound of horses’ hooves approaching. The old woman just had time to return to her seat by the fire before the robbers entered the room. From her hiding place, Aniela saw the robbers drinking and feasting and making merry. She recognised Aleksandr among them, but he was no longer the charming man to whom she had been betrothed. He was just as course and rough as his bandmates, and his voice no longer carried its pleasant tones.

Aniela could also see that they were dragging a young woman, whom they had captured in the forest. She screamed and sobbed and begged for mercy, but it made no difference to the ruthless men. They forced her to drink a glass of red wine, then a glass of white wine, then a glass of yellow wine. It was all too much for her, and her heart burst apart.

The robbers then tore off her fine clothes and laid her body on the table before chopping it to pieces and sprinkling it with salt. Their knives rose and fell, rose and fell, while blood spilled out everywhere. Aniela watched and heard all this from behind the wine casks, but she did not shake with fear, lest she would be noticed. Then she heard a voice speak out above the rest.

“Be still, you rouges!” It was Aleksandr. “You forgot to take off that gold ring on the wretch’s finger.”

“We didn’t see it,” said one of the robbers.

Aleksandr let out an exasperated sight. “Do I have to do everything around here myself?” He tried to remove the ring, but it wouldn’t come off. Finally, in a fit of rage, he hacked the finger off the hand with his knife. The finger flew into the air, tumbled over the wine casks… and landed right into Aniela’s lap. Despite her shock, Aniela managed not to gasp or scream, but instead remained silent. She quickly hid the finger in her pocket.

“Bloody hell! Where’s it gone?” screamed one of the robbers.

“I can’t find it anywhere on the floor,” said another.

“Have you looked behind the wine casks?” said a third. “I think it went over there.”

“Leave it for now!” the old woman intervened. “Come and eat your supper. It’s late and rabbit pie is best when hot. You can look for the finger in the morning — it won’t run away.”

“She’s right,” Aleksandr laughed. “And besides, I need a good hearty meal to take my mind off that wretched bride of mine. She hasn’t come — as expected — and I’m in a rare bad mood. Tomorrow I’ll go to the mill and demand my bride. Her father is a vain, foolish man — he’ll hand her over to me easily. And she better not try any more tricks on me, or else!”

So the robbers gave up their search, pulled up their chairs and sat down to eat and drink. Aniela let out a tiny sigh and waited. Meanwhile, the old woman secretly put a sleeping potion in the jug of wine. It wasn’t long before all the robbers slumped to the floor and fell asleep.

When Aniela heard the robbers snoring, she slowly crept out from behind the wine casks. She had to tread carefully, for the robbers lay sprawled out on the floor, and she was afraid of rousing them. In one corner of the room she saw the remains of their murdered victim and her eyes filled with tears. At last she reached the cellar steps safely, where the old woman was waiting. Aniela took her hand, and together they crept upstairs, stole through the empty rooms and hurried out of the house as fast as they could.

The moon was high and the forest was bathed in silver light as the two made their way through the trees. The wind had blown away the strewn ashes, but the peas and beans, being heavier, remained on the ground. They followed the path all night long, for the woman walked slowly, and in the morning they arrived at the mill.

Aniela told her father everything that had happened, and the old woman confirmed it. The miller was beside himself with rage. He sat down in his chair for a long time to calm down, and at length, he turned to the old woman and said: “You may stay with us for as long as you need. As for you,” he turned to his daughter, “we might as well cancel the wedding and turn Aleksandr and his band to the magistrates.”

“I have a better idea,” said Aniela, and her father could see a wide grin on her face. “While we were walking through the woods last night, I thought up a plan on how to expose Aleksandr and his crimes. If we tell it directly, he might deny it and cover up his tracks.”

She told her plan to her father and the old woman, and they all agreed on it.

***

That afternoon, Aleksandr came again at the mill. This time, however, he was followed by his bandmates.

“Why didn’t you visit me yesterday, as we’d arranged?” he asked Aniela, in his charming, pleasant tone. “My friends here were quite upset that you didn’t come, hence why they’ve followed me here.”

“I had been busy with work, as I told you I would,” said Aniela with the warmest smile she could muster. “But to make up for my absence, we have prepared a feast for you, in honour of the harvest season. Come, we have invited friends and relatives to join our feast so they can meet you as my future husband.”

The robbers, who had awakened to find their housekeeper gone, and had little to eat for breakfast, were only too glad to sit down and enjoy themselves. Little did they know that the old woman was hiding in another room!

Aleksandr sat at the head of the table and charmed everyone with his friendly, witty talk. Only Aniela sat still, saying and eating nothing.

After the meal ended, the miller asked each person to tell a story to entertain the other guests. It was soon a merry gathering, as tale followed tale, some true and some untrue, some from long ago and some from just last week. Soon it was Aniela’s turn to tell a story, but she hesitated.

“Come now, my dear,” sneered Aleksandr. “Haven’t you got a story to tell? Just tell us something.”

Aniela paused, as if in thought. At last she said: “All right. I have no story, but I’ll tell you about a dream. Just a dream that I had. If you wish to listen, I’ll tell it to the end.”

The guests murmured with approval. For in those days, dreams were thought to possess hidden truth. They all leaned forward to listen to her dream, including her bridegroom.

“I was walking in a forest, a deep dark forest, when I came upon a gloomy house. I went inside that house. Not a soul was in sight, but for a robin in a cage, and as I went into the parlour, it called after me. “Be bold,” it cried, “but not too bold.”

“Then I went into the bedchamber, the robin called again, and there I saw a great many chests. They were filled with silver and gold, and many other riches besides.”

“That was my house you dreamt of, my dear,” said Aleksandr, nodding with satisfaction. “I have just such chests. And you would have seen them with your every eyes had you been there yesterday.”

“Then, in my dream, I went into another chamber,” Aniela went on. “The robin called to me again — “Be bold, be bold, but not too bold, lest your blood should run cold” — and in that chamber there were tubs and pails…”

“I too have tubs and pails in my house,” said Aleksandr, “both painted and carved.”

“Tubs and pails indeed,” said Aniela, “but filled to the brim with blood.”

“That isn’t so!” cried Aleksandr, shifting in his seat.

“My dear, don’t worry — it was only a dream,” said Aniela. “At last I went down to the wine cellar, where I met a blind old woman shaking her head. I asked her: “Does my bridegroom live in this house?”

“And the old woman said: “Alas, dear girl, you are in the house of a robber and a murderer. If your bridegroom finds you here, he will kill you, chop you into pieces, cook you and eat you.””

“That isn’t so, and it wasn’t so!” cried Aleksandr, looking towards the door.

“My dear, don’t worry — it was only a dream,” said Aniela. “Then the old woman hid me behind some wine casks, and as soon as she did the robbers came home, dragging a woman with them. They forced her to drink three glasses of wine — one red, one white, one yellow — and that made her heart burst apart so she died. They took off her fine clothes, laid her body on the table, chopped it to pieces and sprinkled salt on it.”

“That isn’t so, and it wasn’t so, and God forbid it should be so!” shouted Aleksandr, turning as pale as a corpse.

“My dear, don’t worry — it was only a dream,” said Aniela. “Then the chief of the robbers saw a gold ring on the woman’s finger. He took his knife and chopped it off, and the finger flew through the air and landed in my lap. And here is that finger, with the ring.”

So saying, Aniela rose from her seat and held up the finger with the ring so that everyone could see.

When he heard these words, Aleksandr knocked the table sideways and sprang from his seat, his men with him. They would have escaped… had not the company leapt upon them, grabbed them and dragged them away. For the miller had chosen his guests well, guests with strong arms and nimble feet.

It is said that the band of robbers were sent to court and hanged for their crimes. It was also said that their riches were confiscated, the robin was freed from its cage, and their house was burned to the ground. But whether or not Aniela finally found her one true love, no one cares to tell.

Author’s Note

It was just another day at summer camp. I had brought with me a copy of Grimm’s Fairy Tales (it was specifically the translation by Edgar Taylor and Marian Edwardes) and I was looking through the contents for a new story to read. I spotted “The Robber Bridegroom”, and, thinking it would be a humorous story like “The Master Thief,” about a woman who discovers her bridegroom is a thief, I began to read it. Suffice it to say, I was both wrong and right. But I was as enthralled by it as I was shocked, and then as now, I find it to be a good gory shocker.

This story belongs to the larger body of “Bluebeard” tales, but it also has its own district tale type, that being ATU-955 “The Robber Bridegroom.” Britain is particularly rich in variants of this tale: Katharine M. Briggs listed eight different variants in her Dictionary of British Folk-Tales.

The most famous of these English variants is “Mr. Fox”, which features a bloody chamber filled with the remains of the robber’s victims, just like in “Bluebeard.” This variant may also be ancient; it was first referenced in Edmund Spenser’s English epic romance The Faerie Queene in 1590, where Britomart comes to a house where the words Be bold, be bold are written on every door, until she reached one with Be not too bold upon it. It was also referenced by Shakespeare in Act I, Scene 1 of Much Ado About Nothing (1598), when Benedick says to Claudio: “Like the old tale, my lord: it is not so, nor ‘twas not so; but, indeed, God forbid it should be so.”

The Grimm Brothers collected their variant from Marie Hassenpflug. It is interesting to note that in the 1812 edition of the story, the miller’s daughter is a princess, the robber is a prince, and his victim is the princess’s own grandmother. My retelling is based on the 1857 edition, but I also borrowed a few details from other variants: the chambers in the robber’s house come from the Norwegian variant by Peter Christen Asbjørnsen, and the robber’s interjections at the feast and the bird’s call are taken from the aforementioned “Mr. Fox.”

In The Watkins Book of English Folktales, Neil Philip hypothesised that the central theme of this tale type is sexual violence: “The imagery of severed hands, cellars of blood and open graves queasily encodes an apprehension of rape and sexual shock that serves in its atmosphere of terror as a warning to young girls and in its denouement as a warning to male predators.” That is indeed one of the angles that has influenced my retelling.

Almost every modern retelling of this story aimed at young readers has toned down its gory details; I kept them intact in my retelling, for to do otherwise would mean to lessen its impact. For more on this tale type, and on the “Bluebeard” story in general, see Casie E. Hermansson’s Bluebeard: A Readers Guide to the English Tradition.

Bibliography

Source Material, Variants and Scholarly Work

Asbjørnsen, Peter Christian. “The Sweetheart in the Wood.” Tales from the Fjeld: A Second Series of Popular Tales. Translated by George Webbe Dasent. Chapman and Hall, 1874.

Ashliman, D. L. “Robber Bridegroom: Tales of Type 955.” sites.pitt.edu, https://sites.pitt.edu/~dash/type0955.html. Accessed 21 June 2024.

Briggs, Katharine M., editor. “Mr. Fox”, “The Cellar of Blood”, “Dr. Forster”, “Bobby Rag”, “The Oxford Student”, “The Lass ‘at seed her own Grave dug”, “Mr. Fox’s Courtship”, “The Girl who got up a Tree.” A Dictionary of British Folk-Tales in the English Language. 2 parts, 4 vols. Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd, 1970-1971.

Carter, Angela, editor. “Mr. Fox.” Angela Carter’s Book of Fairy Tales. 1990, 1992. Virago Press, 2005.

Grimm, Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. “Grimm 040: The Robber Bridegroom.” Translated by D. L. Ashliman. sites.pitt.edu, https://sites.pitt.edu/~dash/grimm040.html. Accessed 21 June 2024.

Grimm, Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. “The Robber Bridegroom.” The Complete Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm. Translated by Jack Zipes. 1987. Vintage, 2007.

Grimm, Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. “The Robber Bridegroom.” The Complete Grimm’s Fairy Tales. Translated by Margaret Hunt, revised by James Stern. 1944. Pantheon Books, 1972.

Grimm, Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. “The Robber Bridegroom.” Grimm’s Fairy Tales. Translated by Edgar Taylor and Marian Edwardes. Project Gutenberg, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/2591/2591-h/2591-h.htm. Accessed 21 June 2024.

Grimm, Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. “The Robber Bridegroom.” Grimm’s Household Tales. Translated by Margaret Hunt. George Bell and Sons, 1884.

Grimm, Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. “The Robber Bridegroom.” Grimms’ Tales for Young and Old. Translated by Ralph Manheim. 1977. Anchor Books, 1983.

Grimm, Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. “The Robber Bridegroom.” Household Stories. Translated by Lucy Crane. 1886. Dover Publications, Inc., 1963.

Grimm, Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. “The Robber Bridegroom.” The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm: The Complete First Edition. Translated by Jack Zipes. Princeton University Press, 2014.

Hermansson, Casie E. Bluebeard: A Readers Guide to the English Tradition. University Press of Mississippi, 2009.

Jacobs, Joseph. “Mr. Fox.” English Fairy Tales. G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1890.

Langrish, Katherine. “‘Childe Rowland’ & ‘The Gyir Carline’: Lost Fairy Tales of 16th & 17th century England & Scotland.” Seven Miles of Steel Thistles, 18 June 2024, https://steelthistles.blogspot.com/2024/06/childe-rowland-gyir-carline-lost-fairy.html. Accessed 21 June 2024.

Philip, Neil, editor. “The Story of Mr. Fox”, “Bobby Rag”, “Doctor Forster”, “Wanted, a Husband.” The Watkins Book of English Folktales. 1992. Watkins, 2022.

Pullman, Philip. “The Robber Bridegroom.” Grimm Tales: For Young and Old. Penguin Books, 2012.

Tatar, Maria, editor. “The Robber Bridegroom.” The Annotated Brothers Grimm. W. W. Norton & Company, 2004.

Zipes, Jack, editor. “Bloodthirsty Husbands and Serial Killers.” The Golden Age of Folk and Fairy Tales: From the Brothers Grimm to Andrew Lang. Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 2013.

Retellings and Adaptations

Gidwitz, Adam. “A Smile as Red as Blood.” A Tale Dark & Grimm. The Penguin Group, 2010.

Lamond, Margrete. “Bold, But Not Too Bold.” Tatterhood and other feisty folk tales. Allen & Unwin, 1999.

Mathias, Robert. “The Robber Groom.” Tales from the Brothers Grimm. Hamlyn Publishing, 1986.

Nye, Robert. “Lord Fox.” Lord Fox and other Spine-Chilling Tales. Orion Children’s Books, 1997.

Podos, Rebecca. “A Story About a Girl.” At Midnight: Fifteen Beloved Fairy Tales Reimagined, edited by Dahlia Adler, Flatiron Books, 2022.

Souci, Robert D. San. “The Robber Bridegroom.” Short & Shivery: Thirty Chilling Tales. Yearling, 1987.

I loved this!! Had never heard of it before and I was so enthralled by it that I was almost scrolling faster than I could read. Thank you!