“Fairy tales can be read twice and in two ways in one's life. First simply, as a child, with the naive belief that the lively, colourful world of their events is true, and then, much, much later, with the full awareness of their invention.”Stefan Zweig, translated by the present writer

“Fairy tales are more than true: not because they tell us that dragons exist, but because they tell us that dragons can be beaten.”Neil Gaiman, paraphrasing G.K. Chesterton1

“Some day you will be old enough to start reading fairy tales again.”C.S. Lewis

“Every fairy tale has someone who believes it.”Karl Friedrich Wilhelm Wander, translated by D.L. Ashliman2

I have loved fairy tales for as long as I can remember. Whereas most children would pester their parents for the newest toy, I would pester mine for the latest illustrated fairy tale book that I found at the bookstore. Even at a young age, I recognised how fairy tales can be transformed yet still retain their essence through both text and art. I certainly didn’t know then that fairy tales were once the domain of adults as well as children, or that there are people who dedicate their careers to discussing them. It was simply something I was deeply drawn to.

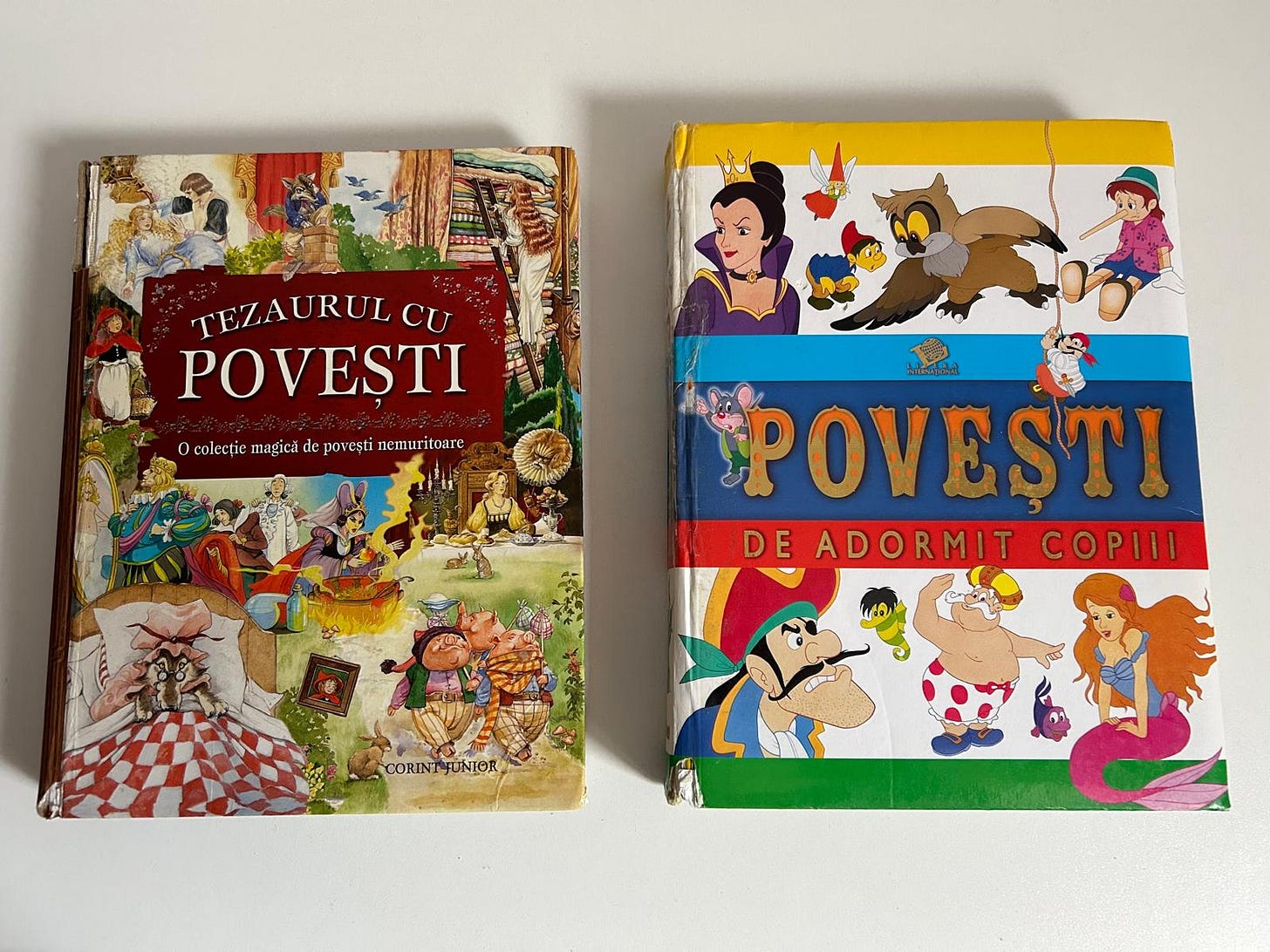

In spite of my ever-growing collection of fairy tale books, I received my first proper treasury of fairy tales — that one book many of us treasure as children and fondly think back to as adults — on my eighth birthday. It was a Romanian translation of Arcturus Publishing’s amply titled A Treasury of Fairy Tales — a bestseller in my country. The beautiful illustrations, the engaging text, and the overall gorgeous design made it a favourite of mine, and I would take it with me wherever I could, just to pore over it once more. This is where, I believe, I first learned the story of “Bluebeard”, but more on that later.

Another favourite fairy tale treasury was an Italian book called Grandi fiabe per sognare — titled Bedtime Stories for Children in the Romanian edition. It was a collection of 25 fairy tales illustrated by Claudio Cernuschi and Maria de Filippo. This is where I was introduced to the story of “The Selfish Giant,” and possibly “The Wild Swans” too. Both of these treasuries are now proudly sitting on my bookshelf. Their age and wear is noticeable, though they are still perfectly functional, and they are both cherished parts of my ever-growing collection.

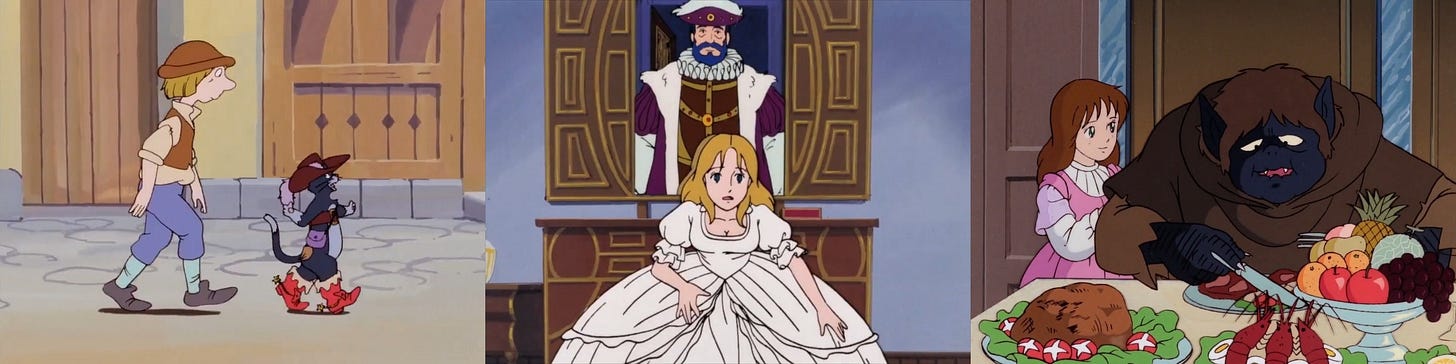

But my love of fairy tales did not pertain only to books; I was (and still am) equally captivated by the myriad ways fairy tales can be adapted for film and television. As a child of the 2000’s, I grew up on shows like Simsala Grimm and The Fairytaler on TV. I watched Toei’s World Fairy Tale Series and the Barbie fairy tale films on DVD. And, when I finally had access to the internet, the very first things I found and watched were Saban’s My Favorite Fairy Tales and Grimm’s Fairy Tale Classics.

By then my knowledge of fairy tales was mostly limited to the perennial classics, as well as a handful of lesser-known stories from Grimm, Andersen, and Perrault. It was around middle school — that awkward phase when you don’t know what you want in life — when I stumbled upon a complete edition of the Grimms’ fairy tales at the school library. It had illustrations by Ludwig Richter, and I was quickly hooked. My experience with these stories was similar to many others’: they were violent and strange, yet oddly comforting and intriguing.

It was also around that time when I was introduced — through the German-language library in my city — to the Märchenfilme: German TV films based on fairy tales, mostly from Grimm. I initially watched the two current fairy tale series — Sechs auf einen Streich (Six in One Strike) and Märchenperlen (Fairy Tale Pearls) — but I later discovered the classics — the Märchen-Klassiker — from DEFA.3 Although their sensibilities were similar to Disney, minus the songs and animation, they were much more faithful to the original tales.

The period between middle school and high school was mostly marked by rediscovery. I got reacquainted with the fairy tale films from Disney, Soyuzmultfilm and others that I had seen when I was younger. I also reread James Finn Garner’s Politically Correct Bedtime Stories, my first proper book of fairy tale retellings. I first read it when I was far too young to appreciate its intent — but now I do. I also read — and fell in love with — my first proper fairy tale novel: Chris Colfer’s The Land of Stories: The Wishing Spell. It served as a great bridge between remembering the classics and revisiting them with different eyes.

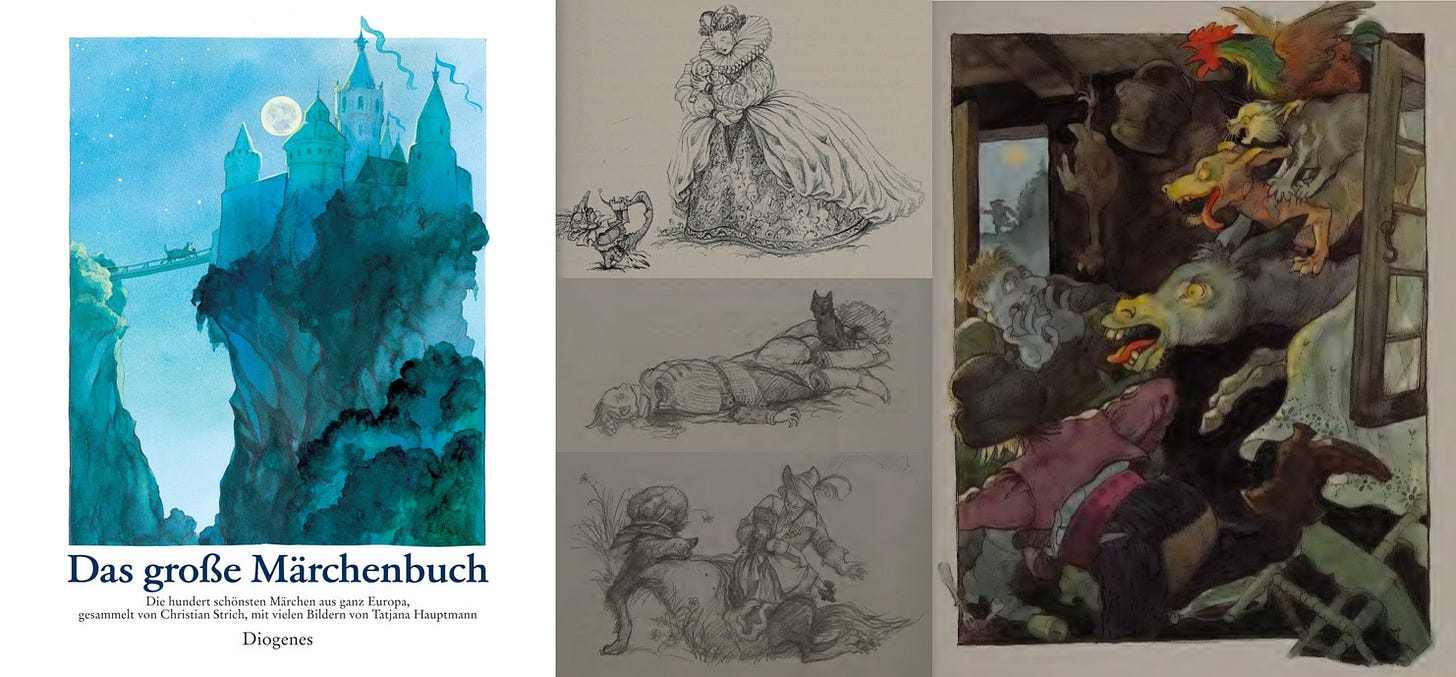

But the book that truly cemented my love of fairy tales was a German anthology that I found in the aforementioned German-language library. It is titled Das große Märchenbuch: Die hundert schönsten Märchen aus ganz Europa (The Big Book of Fairy Tales: The One Hundred Best Fairy Tales from All Over Europe). As the title suggests, it is an anthology of one hundred European folk and fairy tales selected by Christian Strich, and this was my introduction to a whole array of stories and folktale traditions.

Like the Grimm collection illustrated by Richter, this book pulls no punches. All the stories, not just those from Grimm, are both violent and enthralling, and they are accompanied by Tatjana Hauptmann’s gorgeous and haunting illustrations: Prince Ivan’s gruesomely severed body abandoned in the forest (in “Prince Ivan, the Firebird, and Grey Wolf”); Little Red Riding Hood being lifted from the dead wolf’s guts by the hunter; Rumpelstiltskin tearing himself in two before the terrified queen, as she clutches her child; the ghostly image of the Bremen Town Musicians braying and howling at the robbers’ window.

It was this book that inspired me to dive deeper into fairy tales, to research their origins, and to seek out as many retellings and adaptations as I could find. I’m not exactly sure why it was this one that has had such an impact on me — perhaps it was the comprehensiveness of it all? — but it did, and my own copy now proudly sits on my bookshelf as well.

Whatever your opinion on fairy tales is, it is undeniable that they have become an integral aspect of our shared cultural heritage, to the point where it is hard to find someone who doesn’t know at least a couple of them. Perhaps you were told the story of “Little Red Riding Hood” as a child, or you might have found the story of “Rapunzel” in a book, or maybe you saw a film version of “Snow White.” But it doesn’t matter how one first encountered these stories — they all possess a special kind of magic that has kept them alive in our hearts and minds.

Fairy tales also represent storytelling in its purest form, which may explain why we see traces of them throughout all types of fictional media. Popular characters like Captain Jack Sparrow, Bart Simpson, and Bugs Bunny may be seen as successors to trickster characters such as Puss in Boots, Jack (of Beanstalk fame) and the Master Thief. “The Nutcracker” and “The Steadfast Tin Soldier” may be among the earliest instances of sentient toys in fiction, paving the way for subsequent works like the Toy Story franchise. And Cinderella, that reigning queen of fairy tales, has given rise to countless other rags-to-riches stories like Sabrina (1954, 1995), Pretty Woman (1990) and The Princess Diaries (2001).

Stephen King’s novel The Shining references the story of “Bluebeard” both directly (Jack reads the story to his young son Daniel) and indirectly (Jack becomes mad and chases his wife Wendy through the hotel, intending to kill her). Swan Lake — a ballet in which a group of maidens is cursed to be swans by day and humans by night — uses motifs from various fairy tales, one of which no doubt is from a variant of “The Wild Swans.” Bryan Lee O’Malley’s graphic novel series Scott Pilgrim can be seen as a modern fairy tale: the eponymous protagonist has to defeat his girlfriend Ramona’s seven evil exes to be with her, similar to how a prince has to defeat a dragon or monster to get to the princess.

Naomi Lewis suggested that the characters of Toad and Mole from Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows may have been inspired by characters from “Thumbelina.”4 Similarly, critics like Alison Lurie and Katherine Langrish have pointed out that Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre draws from both “Cinderella” and “Beauty and the Beast.”5 Acclaimed authors such as Franz Kafka, Salman Rushdie, and Angela Carter have also incorporated — and subverted — folklore motifs and conventions in their works.6

So fairy tales are everywhere: in fiction, in advertisement, in casual speech. But this leads us to one big question: Why? How do these ancient, seemingly outlandish stories continue to wield such power over us? What is it about them that keeps us coming back? The answer to this question goes much deeper than one might imagine, with a rich history and a myriad of meanings attached to it. So join me as we delve into the perplexing and fascinating world of fairy tales.

What is a Fairy Tale?

“Fairy tale” is a term that has come to be used rather loosely: as a descriptor (“a fairy tale wedding”), as a genre (fairy tale films), and, most of all, as a catchall for classic children’s stories, regardless of whether they’re actual fairy tales or not. Andrew Lang included an abridged version of Book 1 of Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (“A Voyage to Lilliput”) and an adapted version of the myth of Perseus (“The Terrible Head”) in his Blue Fairy Book (1889).

The aforementioned anime series from Toei, World Fairy Tale Series, features adaptations of novels like The Three Musketeers and Gulliver’s Travels alongside Grimm tales like “The Golden Goose” and “The Wolf and the Seven Little Goats.” Samantha Newman’s book Adventure Stories for Daring Girls contains adaptations of novels like Heidi and The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, the ballad of Mulan, the myth of how Athena became the patron goddess of Athens, and classic tales from around the world. The ABC series Once Upon a Time (2011-2018) incorporates novels like Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde and 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, Arthurian legends, Robin Hood and Greek mythology into its cast of fairy tale characters. Animated series like Ever After High (2013-2016) and the first season of Super Why! (2007-2010) feature stories and characters from literary novels, nursery rhymes, fables, and legends.

Because so many non-fairy-tale stories are often conflated with fairy tales — likely due to their inclusion in the broader category of classic children’s stories — it may be useful to first clarify what is not a fairy tale. To do this, I will go over the most common categories of what scholars and folklorists refer to as “folk narratives.” Folk narratives are generally divided into three groups: myths, legends, and folk tales, but further subdivisions exist. These categories can also change form or cross between one another depending on the storyteller’s wishes, who often doesn’t know — or even care — about scholarly distinctions. Still, it it may be useful to make some general distinctions for the sake of clarification.

Nursery Rhymes

Nursery rhymes are almost never brought up in folk and fairy tale studies, but since they are often conflated with fairy tales, I saw fit to include them in this discussion. Nursery rhymes are short, traditional verses typically sung or recited to children. They often contain repetitive phrases and catchy rhythms, making them easier to remember. But whereas fairy tales are full-fledged stories, with a proper beginning, middle, and end, nursery rhymes usually depict just one sequence of events.

Another distinction between fairy tales and nursery rhymes, as Chris Duffy pointed out, lies in their malleably: “The shortness of the nursery rhymes (sic), plus their essence as something spoken or sung, mean(s) that (they are) very interpretive (…). (The telling of fairy tales) is more about adapting and less about interpreting.”7 Furthermore, folk and fairy tales can be told in both prose and verse, whereas nursery rhymes are always presented in verse.

It should also be noted that, even more so than folk and fairy tales, nursery rhymes were originally used as covert critiques of prominent figures of the time. For example, “Humpty Dumpty” may be a reference to “a piece of military weaponry used during the English Civil War,” as Karen Dolby put it, while the events in “Jack and Jill” could be an allusion to the execution of King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette during the French Revolution of 1793.8

Myths and Legends

Myths and legends are closely related genres, as they are both fictionalised accounts of events that claim to be true. Their difference lies in what they focus on. Legends like “Robin Hood” are stories with a historical basis and often involve a specific historical figure (King Richard I of England, also known as King Richard the Lionheart), a specific location (Sherwood Forest in Nottinghamshire, England), or a specific event (the tensions between the aristocracy and the common people in the late twelfth century). While legends may contain supernatural elements (Saint George slaying a dragon), they are typically more human-centred, more specific in time and location, and more local than myths.

Myths, on the other hand, are foundational stories that explain the origins of entities, landscapes, and natural phenomena through the deeds of heroes and deities. Their settings are more ambiguous than those in legends — usually just their country of origin — and they are characterised by their connections to folk or religious beliefs. In the Greek myth of “Athena and Arachne,” the eponymous characters engage in a weaving contest, with Arachne being transformed into a spider at the end. Thus the myth provides a fantastical explanation for the origins of the spider.

Unlike myths and legends, a fairy tale is ambiguous in its setting, taking place in an unspecified distant past with only superficial references to religion and real-life people, places, and events. Some exceptions do exist, however. “The Pied Piper of Hamelin” began as a legend based on historical events and gradually adopted traits that made it more akin to a fairy tale.9 While the story contains magical elements usually found in fairy tales — such as a mysterious stranger with supernatural powers, a magic flute, and an impossible task — it is set in a real place (the German city of Hameln) and it ends with an allusion to historical events (the migration of Germans across Europe). In some adaptations, the historical allusions are omitted, further transforming the story into a more traditional fairy tale.

On a related note, adapting folk and fairy tales differs from adapting myths and legends. While folk and fairy tales reflect the time and place in which they were written, they are also fictitious stories, meaning that storytellers can play fast and loose with the details. The same freedom cannot be applied to legends, and especially myths, as Judy Sierra explained:

“Most myths have as their purpose the justification of a social order that is far from universal or natural, such as one group (…) dominating another. Adapting myths for contemporary audiences poses a real challenge to the storyteller. Taken out of cultural context and altered to appease potential censors, myths become marginally interesting stories that are important only because they are marketed as “sacred tales from such and such a culture.””10

Fables and Animal Tales

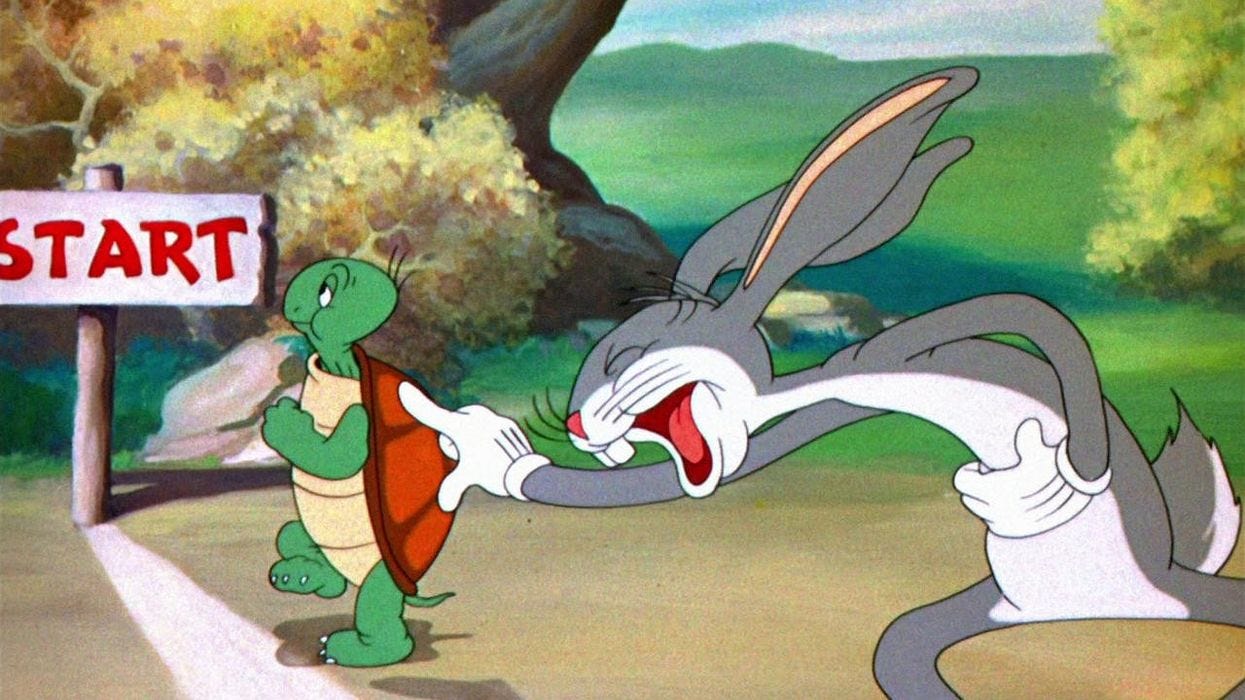

It is often assumed that folk and fairy tales are meant to convey moral lessons, but that is not their primary purpose. Fables, on the other hand, are short stories specifically intended to convey a moral or a message (“slow and steady wins the race”) by way of talking animals, plants, and sometimes people. The fable’s defining features are its humanisation of animals and plants, its brevity, and its didactic nature.

The moral in fables can sometimes be interpretive or dependent on context, as seen, for example, in “The Hare and the Tortoise.” Judy Sierra pointed out that the story’s moral is contradicted by its facts, as “the tortoise’s victory depends upon the hare’s overconfidence,” and so it “serves more as a warning to the swift than as advice to the slow.”11

Fables, along with other folk narratives such as myths, legends, and folk and fairy tales, fall under the broader category of animal tales. The defining feature of all animal tales is their use of anthropomorphised animals as primary characters. In folk and fairy tales, animals usually appear in secondary roles as helpers (“Puss in Boots”) or opponents (“Little Red Riding Hood”), but in some they take on the role of protagonists (“The Three Little Pigs”).

J.R.R. Tolkien did not consider stories like “The Three Little Pigs” to be fairy tales, as he believed that “the animal form is only a mask upon a human face, a device of the satirist or the preacher.” He did, however, view stories with secondary animal characters, such as “Puss in Boots,” as fairy tales because they express “the desire of men to hold communion with other living things.”12 But animal tales like “The Three Little Pigs” are not explicitly didactic; they follow a narrative structure typical of folk and fairy tales and have deep folkloric roots. Variants of “The Three Little Pigs” can be found in countries like America and Turkey, for example.13

Fairy Tale Novels

Despite being occasionally included in fairy tale media, classic novels aimed at adults, such as Gulliver’s Travels and The Three Musketeers, and those aimed at children, such as Heidi and The Jungle Book, are not fairy tales. These novels are much longer in form and present more complex, realistic narratives, whereas fairy tales are shorter and more fantastical in nature.

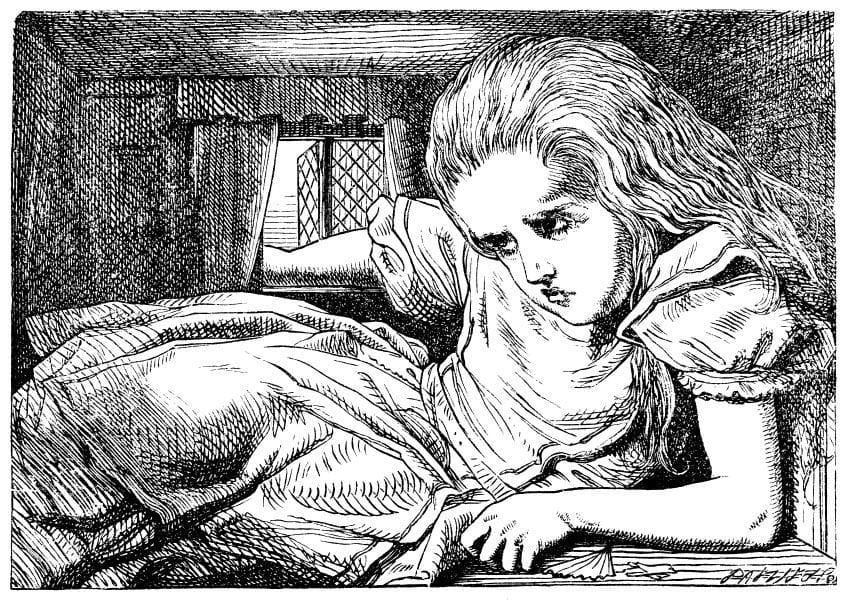

But even with these distinctions in mind, a few classic fantasy novels are frequently categorised as fairy tales in novel form, those being The Adventures of Pinocchio, The Nutcracker and the Mouse King, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, and Peter Pan and Wendy. What all these novels have in common, as Jack Zipes pointed out, is that they “involve young protagonists, who take miraculous journeys and are transformed through their adventures,” and their plots follow “the traditional outlines of the fairy tale’s scheme of departure from home.”14

Even the authors of these works seem to have acknowledged how similar they are to fairy tales. For instance, Carlo Collodi’s Pinocchio begins with the following lines:

“Once upon a time there was…

“A king!” my little readers will no doubt say in a flash.

““No, kids. You got it wrong. Once upon a time there was… a piece of wood.””15

Similarly, in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, after growing large inside the White Rabbit’s house, Alice remarks: “When I used to read fairy-tales, I fancied that kind of thing never happened, and now here I am in the middle of one!”16

L. Frank Baum introduced his book The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by stating that it was intended as a modern fairy tale “in which the wonderment and joy are retained and the heartaches and nightmares are left out.”17 However, this statement is contradicted within the work itself; there is colour and whimsy in Oz, for sure, but there is just as much darkness and danger too. This blend of light and shadow, I believe, contributes to its enduring charm.

There are just as many arguments one can make for why these works should be considered fairy tales as there are arguments for why they should not. It ultimately comes down to one’s perception of these novels. In my opinion, however, I view Peter Pan, Alice in Wonderland and The Wizard of Oz more as fantasy novels rather than genuine fairy tales, as they make a clear distinction between the real world inhabited by the protagonists and the imaginary worlds — Neverland, Wonderland, and Oz — to which they travel. J.R.R. Tolkien pointed out that one of the defining features of a fairy tale is its commitment to presenting its wondrous, fantastical events as true: “Since the fairy-story deals with ‘marvels’, it cannot tolerate any frame or machinery suggesting that the whole story in which they occur is a figment or illusion.”18

Pinocchio and The Nutcracker, by contrast, do embrace their fantastical elements and never make a clear distinction between the real world and the one the characters inhabit, making them genuine fairy tales in my eyes. This view is further supported by the incorporation of folkloric elements within these stories. As Jan M. Ziolkowski argued, they “may not conform to any one tale type, but (they) absorbed many techniques and motifs familiar from folktales, both oral and literary.”19 Pinocchio echoes folk tales like “The Snow Child,” where an inanimate object — a puppet in this case — comes to life, while The Nutcracker reworks the Beastly Bridegroom motif, with a nutcracker’s curse being lifted through a girl’s love and devotion.

Certain works of fiction that feature magic and fantastical beings, like J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, are sometimes described as fairy tales. However, these works more accurately belong to the genre of fantasy, specifically high fantasy. High fantasy stories are characterised by extensive world-building, intricate lore, and detailed histories. In contrast, fairy tales are much simpler narratives, often set in vague, unspecified locations with a focus on universal themes rather than detailed world-building. Moreover, fairy tales are not strictly quest or adventure stories, whereas The Lord of the Rings is fundamentally a quest narrative.

Folk Tales and Fairy Tales

Folk tales, as their name suggests, are the stories of the folk, the common people. These stories originated in the oral tradition, long before people knew how to read or write, and they have no accredited author. In other words, no one knows who first told a particular folk tale, as it was originally transmitted by word of mouth.

Folk tales are generally characterised by human scenarios, rather than magical ones. The characters are far more likely to be common people like peasants and farmers, animals like cunnings foxes and loyal dogs, or a blend of the two. The day is won not by use of magic, but by a clever trick or answer, usually accompanied by a joke or a biting remark.

Because folk tales originated in oral storytelling, their structure can sometimes feel disjointed and repetitive when written down. A story like “Henny Penny,” which relies on repetition to advance the plot, can come across as monotonous in written form. In “The Black Bull of Norroway,” a Scottish variant of “East of the Sun and West of the Moon,” a maiden rides on the back of a black bull, who later leaves her near a valley and never comes back. The second half of the story seems disconnected from the first, as the girl shifts her focus to capturing the attention of a knight. Whether this knight is the bull freed from a curse remains unclear. According to Rosalind Kerven, this narrative inconsistency “signals (the story’s) origin as an oral narrative designed to hold listeners’ attention and remind them of what has gone before.”20 Such storytelling techniques, though effective in oral performances, often lose their impact when written down. As Robert H. Hock explained:

“Telling a folktale is a natural art, but writing a folktale down is an act of translation. (…) It require(s), therefore, an even greater artist to make this rendering live once more, to make this translation from the living voice into a true tale that you could not only hear in your head as you read it but also continue to hear in your ears.”21

This brings us to fairy tales, which, broadly speaking, are a literary subset of folk tales. Fairy tales are characterised by the presence of magic and wondrous elements, rather than — as their name might imply — the presence of fairies. In the words of Mary Hoffman:

“What makes a story a fairy tale is a little bit of magic that stirs the imagination, and it doesn’t matter where it comes from. It can be a pumpkin that is turned into a beautiful coach, a talking animal that can make a wish come true, or a spell that turns a handsome prince into a beast.”22

In spite of this, many of the stories that are commonly recognised as fairy tales — such as “Cinderella,” “Snow White,” and “Beauty and the Beast” — are actually just literary variants of much older folk tales. As such, it can be difficult to separate fairy tales from folk tales.

Further complicating this distinction is the term itself: “fairy tales.” Only a few of the stories commonly recognised as fairy tales — “Cinderella,” “Sleeping Beauty,” and “Pinocchio” — actually feature fairies. Many others, such as “Snow White,” “Jack and the Beanstalk,” and “Rapunzel,” feature different magical beings like witches, giants, and elves. This is because the fairies most commonly associated with these tales come from the French tradition. In contrast, the Fae folk of the British Isles, as depicted in stories like “Kate Crackernuts” and “Burd Janet and Tam Lin,” are often portrayed as fickle, dangerous beings, far removed from the benign, godmotherly fairies we typically imagine.

The term “fairy tales” originates from the French phrase “contes des fées,” coined by Marie-Catherine d’Aulnoy in the seventeenth century. At that time, fairies played a vital role in many stories, so d’Aulnoy used the term — which directly translates to “tales of the fairies” — to describe her works. The word “fairy tales” first appeared in English in 1749, but it only gained widespread usage in the latter half of the nineteenth century, particularly through English translations of d’Aulnoy’s and the Grimms’ stories.23

Over time, scholars have debated the accuracy of the term “fairy tales,” arguing that it is somewhat misleading, as these stories are defined more by a sense of magic and wonder than by the presence of fairies. Some have suggested alternative terms like “magic tales,” “wonder tales,” or the more encompassing “folk tales.”24 Others believe that “fairy tales” remains an appropriate term. Steven Swann Jones, for instance, contended that the term effectively refers to stories that “depict the world of magical fantasy.” Jones further explained: “Since, in the English folk tradition, the fairy realm is the embodiment of the magical aspect of the world, (the term “fairy tales”) is used metonymically to refer to all folktales that incorporate the magical and the marvelous.”25 Similarly, Martin Hallett and Barbara Karasek argued that “fairy tales” serves as a helpful compromise between oral folk tales and literary tales.26

For the purposes of this discussion, I will be using “fairy tales” to refer to stories rooted in the literary, magic-focused folklore tradition, “folk tales” for the oral, global folklore tradition, and “folk and fairy tales” as a general term encompassing both.

In the introduction to Favorite Folktales from Around the World, Jane Yolen identified three types of folk and fairy tales,27 which are:

Oral Tales (“Stone Soup”): These tales remain closely connected to their folkloric roots, existing in numerous versions without any one “authoritative” text.

Transcribed Tales (“Rumpelstiltskin”): While these tales also have folkloric origins, they have been significantly reshaped and “tidied up” by known authors or collectors in the course of their preservation.

Literary Tales (“The Reluctant Dragon”): These are original stories that draw on motifs and conventions from traditional tales.

Building on this classification, I’ll borrow from Andrew Teverson28 and introduce a fourth type:

Artful Tales (“Beauty and the Beast”): These stories are based on or inspired by traditional tales but are so creatively told that they feel like original narratives. They stand between transcribed and literary tales.

While these distinctions are valuable for scholarly purposes, the origin of a tale — whether oral or literary — is ultimately secondary; a good story is a good story, regardless of its origins.

The World of Fairy Tales

Jean Cocteau opened his iconic 1946 film La Belle et la Bête (Beauty and the Beast) with a direct appeal to his viewers:

“Children believe what we tell them. They have complete faith in us. They believe that a rose plucked from a garden can plunge a family into conflict. They believe that the hands of a human beast will smoke when he slays a victim, and that this will cause the beast shame when a young maiden takes up residence in his home. They believe a thousand other simple things. I ask of you a little of this childlike simplicity and, to bring us luck, let me speak four truly magic words, childhood’s “Open Sesame”: Once upon a time…”29

By this Cocteau didn’t imply that “Beauty and the Beast,” or any other fairy tale, should be treated as a mere children’s story. Rather, he suggested that these stories should be viewed not as ordinary works of fiction, but as expressions of the human imagination. Children, with their curious and open minds, may ask questions, but they are often more willing to accept the fantastical nature of these tales than adults, who are constrained by logic and reason.

Fairy tales take place in a strange, marvellous world dominated by magic. In this realm, ordinary people live alongside all manner of magical beings: witches and sorcerers, giants and trolls, fairies and elves, dragons and mermaids. The trees and animals of the forest can not only talk, but, like Puss in Boots, can be far wiser and cleverer than human beings. There are castles that stand atop glass mountains, enchanted objects that can grant wishes, and winged horses that fly through the sky. Here, people can be transformed into bears, frogs, and swans, and then back again. Anything can happen in the world of fairy tales.

Take the story of “Prince Ivan, the Firebird, and Grey Wolf.” It begins with a king who owns a tree that bears golden apples. To a rational mind, this immediately raises questions. How can a tree produce golden apples? Where did it come from? How did the king procure it? But such questions miss the point. Magic in fairy tales is not explained but implied, focusing not on how it came to be, but on how it effects the lives of those who possess it. As Marina Warner put it: “The power of (a fairy tale) lies in its ineluctability: nobody asks why things should be so.”30 Enchanted trees and magic mirrors are as normal in the world of fairy tales as cars and computers are in our current modern world.

Magic in this world may defy human logic, but it is not arbitrary. At the stroke of midnight, Cinderella’s dress turns back into rags. A hand-mill will only work and stop when the correct magic words are spoken. In “The Wild Swans,” Eliza’s brothers are turned into swans, and to break the spell, she must sew shirts from nettles without uttering a single word. At the end of her labour, the last shirt lacks a sleeve, so the youngest brother is left with a wig instead of an arm. Magic here is inviolable, and it cannot be abused. A fisherman’s wife, dissatisfied with her lot, demands ever greater riches: first a cottage, then a mansion, then to be a queen, then to be an empress, and finally to be a god. Her last wish is too much, and so everything reverts back to the tiny hovel she began with.

But amidst all the glimmer and glamour, this world can be a dark and dangerous place. Children are mistreated and abandoned, lovers are separated from each other, and the poor and weak are exploited by those who should protect them. In this world, it doesn’t matter if an animal can talk — the food chain still applies. Appearances can often be deceiving: a tempting gingerbread house may be a trap set by a hungry witch; a silver-tongued wolf or a well-to-do gentleman may conceal sinister intentions; a gentle, alluring water nixie may offer you wealth and salvation, but at a terrible cost: the person you cherish most.

But the reverse can also be true: a half-hedgehog half-human creature may be far more honourable than a mighty king; a scruffy, ragged princess could be the one to drive away those pesky invading trolls; that booming giant or ferocious beast living in a deserted castle may just be a lonely, gentle soul with a terrible temper.

When rules or conditions are imposed, they are bound to be broken in some way. Bluebeard forbids his wife from opening the forbidden door, but her curiosity compels her to do it. The Little Mermaid is warned by the Sea Witch that if the prince does not return her love, she will turn into sea foam — and indeed, he falls for another. Aleodor is cautioned by his father to avoid the mountain of Half-Man-Half-Lame-Hare, yet he ventures there heedlessly. But even when these warnings are disregarded and danger follows, the characters always find a way to overcome their fate.

To succeed in this world, you’d need quick thinking, courage, and resilience. Emotional strength is valued over physical strength, and journeys and quests take precedence over battles. It is also advisable to help those in need, for who knows who you might encounter along the way. The freezing bear you shelter during a snowstorm may be a prince under a spell; the frail old woman you share your bread with could grant your heart’s deepest wish. In the realm of fairy tales, anything is possible.

The Fairy Tale Rite of Passage

It would be remiss to generalise fairy tales too much, as they are defined just as much by their exceptions as by their rules. A wolf might pursue a little girl in a red cape or go after seven little goats, but he could just as easily assist a prince in finding a firebird or help a sheepdog regain his owners’ favour. While helping those in need is advisable, caution is equally important: when Snow White shows kindness to an old woman, her good deed is turned against her, resulting in her poisoning. Fairies usually appear to assist those in need, as seen in “Cinderella” and “Ricky Tuftyhead,” but they are not always benevolent. In “Catherine and her Fate,” Catherine’s Fate causes her endless trouble until it becomes too much, while Sleeping Beauty’s destiny is shaped by both good and wicked fairies.

Still, a fairly consistent, though not universal pattern can be identified in fairy tales, as noted by structuralist scholars like Vladimir Propp in Morphology of the Folktale.31 Fairy tales often begin with a young adult or child in a disadvantaged position. A boy may be the youngest of three brothers (“Puss in Boots”), often regarded as a fool by others (“The Little Humpbacked Horse”) or seen as incapable of measuring up to his older brothers (“Prince Ivan, the Firebird, and Grey Wolf”). Similarly, a girl may find herself in the lowest position in the family (“Cinderella”), or may be forced to leave home by circumstance (“Cap o’ Rushes”) or by necessity (“Thousandfurs”).

From this humble starting point, the story unfolds and the protagonist metaphorically leaves the safe confides of childhood and ventures into the unpredictable terrain of adulthood. This transition is typically marked by a quest, a pursuit of fortune, or a series of daunting tasks. This represents a “rite of passage,” as Carl Lindahl called it, “a ritual marking a person’s transition from one state to another — from childhood to adulthood, for instance.”32

This rite of passage in fairy tales generally follows a three-part ritual, well exemplified in the story of “Snow White”:

Separation: Snow White is cast out of her home, the castle, and must venture into the forest alone.

Initiation: She finds refuge with the seven dwarfs, but her ordeal isn’t over. The wicked queen subjects her to a series of life-threatening “tests,” which lead Snow White through a process of maturation.

Return: Once she has matured and grown wiser, Snow White returns to the castle, ready to assume a new, more autonomous role in society.

Sometimes the protagonist is faced with a seemingly impossible task, but that is when the magical helper comes in. The magical helper — a fairy godmother, a talking wolf, a kind old man — is one of the most misunderstood characters in folk and fairy tales. Some view the helper as merely fulfilling the protagonist’s desires while the protagonist passively stands by. It must be pointed out, however, that the protagonist earns the helper’s assistance through actions: the girl from “East of the Sun and West of the Moon” is aided by three old women during her quest, while the boy from “Three Perfect Peaches” receives a magic whistle after kindly sharing one of his peaches with an old woman. As Joanna Cole explained:

“The heroes’ relationships with the magical helpers can be understood as their willingness to partake of what their surroundings have to offer, their acceptance of good fortune when it comes their way, and even their reliance on parts of their own nature not under their conscious control. Theirs is an attitude of trust, or faith, in the world, without which life is a bleak business indeed.”33

The actions of the protagonists stand in direct contrast to those who refuse to help (like the older brothers in “Three Perfect Peaches”) or those who offer assistance only when it benefits them (as the lazy sister does in “Mother Holle”).

Over the course of the story, the protagonist manages to overcome obstacles and ultimately achieves perfect happiness. In fairy tales, the good can triumph over the wicked, and the humble can outwit the proud. A lazy, good-for-nothing rascal like Jack in “Jack and the Beanstalk” can become a daring hero, a lonely “ugly” duckling can find a loving family, and a poor, forsaken peasant may accomplish extraordinary feats. This optimism in fairy tales, with their hope for a better tomorrow, is perhaps why certain people, like psychologist Bruno Bettelheim, insist that fairy tales always end happily. A story that ends tragically, like Andersen’s “The Little Match Girl,” is not a fairy tale in Bettelheim’s eyes, because it does not “convey the feeling of consolation characteristic of fairy tales at the end,” while a happier literary tale like Andersen’s “The Snow Queen” “comes quite close to being a true fairy tale.”34

Here I muss stress again that fairy tales are defined not only by their rules but also by their exceptions. Aside from Andersen and Oscar Wilde, whose stories often end sadly, one can find fairy tales by the likes of d’Aulnoy (“The Yellow Dwarf”) and the Grimms (“Cat and Mouse in Partnership” and “The Singing Bone”) where the protagonists meet a tragic end. But even in those rare instances, there is a strangely uplifting element to the whole ordeal, as if to remind us that life goes on beyond darkness and despair. Fairy tales are anchored in what I’d call realistic hope — they offer no false promises about life, but they still provide consolation and encouragement.

For fairy tales are more than just wish-fulfilling fantasies: the protagonists achieve perfect happiness only after they overcome trials and tribulations. In many ways, folk and fairy tales present us with the worst-case scenarios: What if your parents abandoned you in the forest? What if your child was the size of a thumb? What if the person you love most is taken away from you? By placing these dilemmas in fantastical realms and conveying them through symbols, motifs, metaphors, and archetypes, folk and fairy tales give us a way to express our deepest fears and desires without ever needing to name them directly. They also inspire us to use our wits, to show kindness to others, and to find the courage to face the monsters in our lives, all while shaping our understanding of the world — and ourselves.

Narrative and Character Patterns in Fairy Tales

C.M. Woodhouse deftly pointed out the dark nature of folk and fairy tales as well as their moral ambiguity:

“The point about fairy-stories is that they are written not merely without a moral but without a morality. They take place in a world beyond good and evil, where people (or animals) suffer or prosper for reasons unconnected with ethical merit — for being ugly or beautiful respectively, for instance, or for even more unsatisfactory reasons. A little girl sets out to do a good deed for her grandmother and gets gobbled up by a wolf; (…) dozens of young princes die horrible deaths trying to get through the thorn-hedge that surrounds the Sleeping Beauty, just because they had the bad luck to be born before her hundred-year curse expired; and one young prince, no better or worse, no handsomer or uglier than the rest gets through merely because he has the good luck to arrive just as the hundred years are up; and so on and so on. (…)

“For all this is related by the fairy-story tellers without approval or disapproval, without a glimmer of subjective feeling (…). They never seek to criticise or moralise, to protest or plead or persuade; and if they have an emotional impact on the reader, as the greatest of them do, that is not intrinsic to the stories. They would indeed only weaken that impact in direct proportion as soon as they set out to achieve it. They move by not seeking to move; almost, it seems, by seeking not to move.”35

There is a common misconception that all fairy tale characters are either purely good or entirely wicked. Yes, folk and fairy tales often operate within a clear good-versus-evil dynamic, but a closer reading reveals many shades of grey woven throughout these stories.

Both the princess and the frog in “The Frog Prince” display vanity and selfishness: the princess by breaking her promise and the frog by taking advantage of her predicament. Goldilocks, a seemingly innocent little girl, breaks into the home of a seemingly fearsome family of bears. Rapunzel’s parents give up their child in exchange for some herb. The wicked queen from “Snow White” seems to be driven by desperation and insecurity rather than pure evil.

“Rumpelstiltskin” features a cast of morally questionable characters: a miller who, out of greed, brags about his daughter and gets her in trouble; a king who imprisons a girl and forces her to perform an impossible task on pain of death; a little man who takes advantage of a helpless girl to claim her child; and a girl who does not seem to consider the consequences of her own decisions.

Hansel and Gretel’s father seemingly loves his children, yet he is complicit in their abandonment, too weak-willed to protest in their defence. Also weak-willed is the fisherman from “The Fisherman and his Wife,” who, out of fear, does everything his wife demands, no matter how outrageous. Maria Tatar observed that in “The Emperor’s New Clothes,” the narrator “adopts no clear point of view, neither endorsing the ingenuity of the swindlers nor defending the vanity of the emperor.”36

Then there are trickster characters like Puss in Boots, Jack from “Jack and the Beanstalk,” and Molly Whuppie, who lie, steal, and deceive to achieve their goals. At first glance these stories seem to go against the core values of folk and fairy tales, but it’s important to remember that trickster tales such as these operate outside the typical good-versus-evil system. Bruno Bettelheim aptly referred to them as “amoral fairy tales” and described them as follows:

“Such tales or type figures as “Puss in Boots,” who arranges for the hero’s success through trickery, and Jack, who steals the giant’s treasure, build character not by promoting choices between good and bad, but by giving the child the hope that even the meekest can succeed in life. After all, what’s the use of choosing to become a good person when one feels so insignificant that he fears he will never amount to anything? Morality is not the issue in these tales, but rather, assurance that one can succeed.”37

In my experience of working with children, I’ve found that many are naturally mischievous, so seeing a character with similar traits can be exciting for them. I also like this quote by Bob Hartman, which places trickster tales in context and emphasises their widespread appeal:

“Some people may question the value of such stories and worry that they promote deceitfulness. But I would rather focus on the origin of those tales. Stories about rabbits tricking foxes usually come from cultures where one group had dominated or exploited another. The smaller creature becomes a figure of hope — using what it has (usually only its quick wits) to overcome a more powerful adversary. Understood in this context, these stories are about much more than brain over brawn. They are about dignity and resourcefulness. And better still — they are lots of fun!”38

This is not to suggest that fairy tale characters are more complex than they seem — their strength lies in their simplicity. Fairy tales do not follow the same rules that we expect from a novel, nor should they be judged by those rules. Fairy tale characters are both particular individuals and universal archetypes. When we see a girl in a red cape, a cat in boots, or a boy made of wood, we instantly recognise them as Little Red Riding Hood, Puss in Boots, and Pinocchio. But these characters are often two-dimensional, defined by just a few adjectives: the big bad wolf, the valiant prince, the benevolent fairy. Their motives are clear from the start, and they rarely, if ever, develop or change; anything that happens to them occurs on the outside.

They seldom have names of their own, and if they do, they are either descriptive, like Thomas Treefork or Snow White, or extremely common ones, like Gretel or Jack. Otherwise they are known by their profession or social status, such as “the princess,” “the old soldier,” or “the youngest son.” Certain characters come in sets of multiples: three little pigs, six mermaid sisters, seven swan brothers, twelve dancing princesses. Unless one of them is the protagonist or a crucial figure in the story, they are virtually indistinguishable from one another.

Philip Pullman suggested that the most fitting visual representation of fairy tale characters is found in silhouette figures, such as those seen in the films of Lotte Reiniger: “Only one side of them is visible to the audience, but that is the only side we need: the other side is blank. They are depicted in poses of intense activity or passion, so that their part in the drama can be easily read from a distance.” Pullman further pointed out:

“None of the information you’d look for in a modern work of fiction — names, appearances, background, social context, etc. — is present (in a fairy tale). And that, of course, is part of the explanation for the flatness of the characters. The tale is far more interested in what happens to them, or in what they make happen, than in their individuality.”39

Like their characters, fairy tale narratives don’t follow the same rules we expect in other types of stories. Descriptions are sparse and abstract, dialogue is minimal, and the action is swift and often contrived. There is no reflection or deliberation; the tale says only what is necessary, nothing more, nothing less. In many ways, fairy tales follow a kind of dream logic: strange events unfold without rhyme or reason, yet they also feel oddly familiar, as if mirroring the subconscious thoughts and emotions within us.

Folk and fairy tales are metaphorical stories, so taking them at face value risks missing their deeper meanings. An example of this can be seen in Vivian Vande Velde’s The Rumpelstiltskin Problem, a collection of retellings of the “Rumpelstiltskin” story. In her introduction, Velde lambasted the original story’s logic and the motivations of its characters. Among her many complaints, she questioned why Rumpelstiltskin demands the miller’s daughter’s ring, necklace, and eventually her child, in exchange for spinning straw into gold:

“Here’s someone who can spin an entire roomful of straw into gold. Why does he need her tiny gold ring? Sounds like a bad bargain to me. (…) Why he wants (her) child he never says, and she never asks.”

Velde concluded her rant by stating: “What do you think your teacher would say if you handed in a story like that? I think you’d be lucky to get a D—. And that’s assuming your spelling was good.”40

However, as Maria Tatar explained, this kind of literal critique misses the deeper, metaphorical logic of the tale:

“Escalating demands are typical of fairy-tale helpers. They ask for something trivial to start with, then move to something that is beyond the norm of an economy of bartering. The helper or donor quickly moves into the role of villain.”41

Folk and fairy tales operate on emotional — rather than logical — rules. These rules may not be immediately apparent, but they become clear once we recognise that the events are metaphors for real-life experiences and concerns. In the case of “Rumpelstiltskin,” the titular character’s increasing demands — from a ring to a child — can be seen as an allegory for manipulation and exploitation, akin to how a drug dealer lures someone in with something small, only to later demand much more as the victim becomes trapped. Rumpelstiltskin’s behaviour reflects the way some people exploit others’ vulnerabilities for personal gain.

Another example can be found in “The Nixie of the Pond,” where a woman seeks to rescue her husband from a water nixie’s grip. After failing to convince the nixie to free him, the woman falls asleep and dreams of climbing a steep mountain to a cottage inhabited by an old woman. Upon waking, she follows this dream and finds the very cottage, where the old woman — seemingly a good witch — provides her with magical objects to aid her quest.

At this point many questions arise: Who is this old woman? Why is she willing to help? How will the items she gives — a comb, a spinning wheel, and a flute — free the woman’s husband? And why did the woman dream of her in the first place? The explanation lies in the emotional logic of the story. The woman’s love for her husband is so powerful that it enables her to succeed, even through magical means. The details of how events happen are less important than why — the focus is on the strength of the woman’s love and her determination to save her husband. As David Holt beautifully explained:

“Most adults have been through many changes themselves and relate to the complexity and difficulty of the relationship in this tale. (…) This is one of those stories that can’t be completely explained but rather is felt on some deep level.”42

Once again, exceptions do exist, particularly in literary tales by the likes of Andersen, where the characters are slightly more complex, and descriptive passages are woven into the narrative. This highlights one of the key differences between literary and oral tales. What they all have in common, though, is their language, which is simple, but not primitive; evocative, but not florid; child-friendly, but not patronising.

Fairy tales often break the conventions of what is typically considered a “good” story, but that is not necessarily a bad thing. In fact, some of the best stories do just that. Above all, fairy tales persist in our collective conciseness through the vivid imagery they evoke: Rapunzel’s long hair tumbling from the tower; Jack climbing the beanstalk to the castle in the clouds; the three dogs summoned by the magic tinderbox, one with eyes as large as teacups, another with eyes as big as mill-wheels, and a third with eyes as big as a tower. These are powerful, symbolic images that carry deep layers of meaning and interpretation. As Idries Shah observed, folk and fairy tales have “a surface meaning (perhaps just a socially uplifting one) and a secondary, inner significance, which is rarely glimpsed consciously, but which nevertheless acts powerfully upon our minds.”43

Another misconception is that fairy tales always have a moral. Yes, a moral can be drawn from them, but it is not always clear what that moral is, or if there is one at all. Take “The Princess and the Pea” for example. Does the story suggest that a “true” princess is defined purely by her delicacy and sensitivity? Or does it subtly call attention to the absurdity of the whole situation, showing how far the queen will go to determine the princess’s nobility? And for that matter, what makes a “true” princess, if not royal linage?

Fairy tales are thus interpretive in nature, and what massage they’re trying to convey is up to the individual to determine. As Neil Philip explained, each fairy tale “can be read as a spiritual allegory, as political metaphor, as psychological parable, or as pure entertainment. (…) The multi-layered quality of a fairytale text is resistant to any single simplified meaning.”44 What all folk and fairy tales share, however, is a sense of hope and a metaphorical reflection of the human experience.

But this still doesn’t fully answer the question I raised at the beginning: why do folk and fairy tales continue to persist in our culture, despite their chaotic, rule-breaking structure? The best explanation lies in their dual nature: they are both universal and personal stories. They reflect the collective experiences of a culture while also portraying the unique journey of a single person. The characters represent both the everyman and the individual, and the simple yet evocative language ensures these stories resonate with people of all ages.

In short, the fairy tale’s typical features can be outlined as such: a protagonist starts out inexperienced but, through a series of events, matures and becomes wiser. The protagonist is accompanied by a cast of characters who play a variety of roles: helpers, adversaries, or both. There is a sense of a bygone time and place baked into the events. A curse is broken by an act of kindness and courage, and, sometimes, love starts to blossom. Harsh reality is acknowledged alongside joy, and some elements are left up to interpretation.

In other words, fairy tales reflect real life, in all of its shades and complexities, in such a way that every person, regardless of age or background, can understand and relate. They reflect like a mirror the best and the worst that we all have: jealousy and greed, loyalty and love, kindness and courage, disobedience and cunning. But they wouldn’t be around if they didn’t entertain as well; how a story is told matters just as much as what it tells.

A Brief History of Fairy Tales

In his pioneering essay “On Fairy-Stories,” J.R.R. Tolkien introduced the concept of “the Cauldron of Story,” which he described as such:

“Speaking of the history of stories and especially of fairy stories we may say that the Pot of Soup, the Cauldron of Story, has always been boiling, and to it have continually been added new bits, dainty and undainty. (…) But if we speak of a Cauldron, we must not wholly forget the Cooks. There are many things in the Cauldron, but the Cooks do not dip in the ladle quite blindly. Their selection is important.”45

Angela Carter later expanded on Tolkien’s metaphor, reshaping it into her own concept of “Potato Soup”:

“Ours is a highly individualized culture, with a great faith in the work of art as a unique one-off, and the artist as an original, a godlike and inspired creator of unique one-offs. But fairy tales are not like that, nor are their makers. Who first invented meatballs? In what country? Is there a definitive recipe for potato soup? Think in terms of the domestic arts. ‘This is how I make potato soup.’”46

Though using different metaphors, both Tolkien and Carter express the same idea — the way humans have continually borrowed, reshaped, and repurposed ideas and materials to create stories. This process is much like how oral folk tales have been passed down through the ages, but for now, I’ll refer to them simply as “stories.”

Since the dawn of time, people have told each other stories — after long days of work, usually around campfires, or just to while away the time. Travellers told stories to make journeys seem shorter. Women told stories to make tasks like spinning more pleasant. Along with music-making and dancing, storytelling was one of the few sources of entertainment people had at the time — and one of the most cherished.

Storytelling was a major source of community, with each story serving a different purpose. Some stories, like “Why the Sea is Salty” and “The Half Chicken,” provided imaginative explanations for natural phenomena, such as why seawater is salty, or the origins of the weathervane, long before the emergence of science. Incidentally, folklorists refer to this type of story — folk tales with a mythological ending — as an etiological tale. Other stories, like “Little Red Riding Hood,” had an educational purpose, teaching children about the dangers of the world, especially at a time when forests were much more perilous places than they are now. Many stories sought to rationalise the fears of an unknown world or impart folk wisdom — the customs, values, and cultural traditions of a people. But above all, they were meant to entertain, to console, to inspire, and perhaps to provide food for thought.

Contrary to certain notions, these stories were not merely escapist entertainment; they served a much deeper purpose. At a time when survival was uncertain, stories provided not just temporary distraction but emotional strength as well. In the aforementioned essay “On Fairy-Stories,” Tolkien defended the value of escapism and hope in the fantasy genre by using allegory:

“Why should a man be scorned, if, finding himself in prison, he tries to get out and go home? Or if, when he cannot do so, he thinks and talks about other topics than jailers and prison-walls? The world outside has not become less real because the prisoner cannot see it.”47

This idea is powerfully illustrated in the Cartoon Saloon film The Breadwinner (2017). Parvana is a young girl living in Taliban-controlled Afghanistan, where females are not allowed to leave their homes without being covered and accompanied by a male. When her father is imprisoned and the only other male in the house is her baby brother, Parvana makes a difficult decision. She disguises herself as a boy to support her family, while living in constant fear of being discovered by the authorities.

Throughout the film, Parvana tells a story to her family and her friend Shauzia, who is in a similar situation. It is about a boy who embarks on a quest to defeat an evil elephant and save his people from a drought. The story doesn’t solve her real-life problems, but it provides a much-needed escape, if only for a little while. We later learn that the story also mirrors Parvana’s own struggles, giving her and those around her the courage to keep going. It is this unique quality — not merely distracting from reality but helping people face it with renewed strength and hope — that has made storytelling such a powerful and cherished art form.

As these stories were originally shared by word of mouth, they often had repetitive patterns — usually in sets of three — and recurrent motifs to make them easier to remember. And they weren’t just for children: everyone in the community heard them, remembered them, and then passed them on. Storytellers would recall the best of the stories they heard and adapt them to suit the tastes and customs of the audience. It was in this way that stories were handed down from person to person, across time and place, changing a little with each new telling. Some details were omitted while others were added or embellished. Names changed and so did places. As a result, we can find variations of the same story or theme all over the world.

For example, in the most common versions of “Puss in Boots,” primarily those from Western Europe, the titular character is a cat. But in Scandinavia, Eastern Europe, and parts of Asia, the protagonist is a fox; in India, it is a jackal; in the Philippines, a monkey; in East Africa, a gazelle.48 Likewise, the brothers in “The Wild Swans” are turned into various kids of birds, depending on the version you come across: swans and ravens, ducks and geese, doves and eagles, and even parrots in Surinam.49

To better illustrate the ever-changing nature of folk and fairy tales, I’ll share one right here: “The Conceited Little Mouse,” a well-known Spanish folk tale. The story exists in many different versions, but they all begin the same way: a little mouse is sweeping the front of her house when she finds a gold coin. She deliberates on what to buy, and eventually decides on a pretty ribbon to tie around her tail. This attracts the attention of several male suitors, who ask for her hand in marriage. To each of them, the little mouse asks to hear their call — the barking of the dog, the braying of the donkey, the crowing of the rooster — and dislikes every single one of them. She is finally won over by the cat’s gentle meowing and charming manners, so she agrees to marry him — only to discover that he intends to eat her!

This is where the story diverges. Traditional versions end with the cat eating the mouse, while others have the mouse escaping from the cat’s clutches, either on her own or with the help of neighbours. More modern versions, typically told to children today, end with a male mouse saving the female mouse from the cat, leading to their marriage and a happy life together.50 In Latin American versions, the mouse is named Martina, and she might be an ant, a butterfly, a cockroach, or a rat, while her suitor is Ratón Pérez, a mouse. They happily marry, without the threat of a sneaky cat, and go on further adventures together.51

And this is how folk and fairy tales have endured over the years — by always changing, always evolving, always coming up anew. Some details may be forgotten, others may be added, but the core essence of the stories remains the same.

Early Instances of Folk and Fairy Tales

Because folk and fairy tales originated in the oral tradition, their history is difficult to trace. However, written evidence has shown that these stories have existed for thousands of years, though not in the forms they are recognised today.

The Odyssey is often regarded by scholars as an early example of a folk tale. Although it belongs to the broader genre of epic, the episode where Odysseus confronts the Cyclop Polyphemus is considered one of the first instances of the trickster narrative.52 More famously, the myth of “Cupid and Psyche,” which appeared in the second century AD in Apuleius of Madaura’s The Golden Ass, is the earliest known literary version of “Beauty and the Beast”, as well as other animal bridegroom stories such as “East of the Sun and West of the Moon” and “The Frog Prince.”53 Scholars like Graham Anderson and Jan M. Ziolkowski have also found early traces of folk and fairy tales in the classical works of Ancient Greece and Rome, as well as in Medieval Latin literature.54

The Hebrew Book of Tobit (circa 600 BC) contains a variant of the “Grateful Dead” cycle of stories, to which “The Traveling Companion” belongs.55 The Panchatantra, an ancient collection of Indian fables from the third century AD, contains some of the earliest versions of stories like “The Three Wishes” and “The Town Mouse and the Country Mouse.”56 Another collection of Indian legends and folk tales, The Ocean of the Streams of Stories by the Brahmin Somadeva Bhatta, compiled in the eleventh century AD, contains episodes that echo motifs from tales such as “Bluebeard” and The Thousand and One Nights, as well as early variants of stories such as “The Princess and the Pea.”57 Some of William Shakespeare’s plays incorporate elements from old folk tales: “King Lear” draws partly on “Love Like Salt” tales such as “Cap o’ Rushes,” while “Cymbeline” borrows from versions of “Snow White” and “The Wild Swans.”58 The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer and The Decameron by Giovanni Boccaccio both include narratives reminiscent of traditional folk tales.59

The oldest recorded fairy tale is believed to be the story of “Anpu and Bata,” found in ancient Egyptian papyri dating back to the twelfth century BC. This tale bears similarities to the Grimms’ “The Two Brothers,” as well as to stories from many other countries. The oldest recorded folk tale, on the other hand, is “The Smith and the Devil,” which dates back 6.000 years to the Bronze Age. This story is about a blacksmith who makes a pact with the Devil, trading his soul for supernatural abilities, only to later renege on the deal by using his powers to trap the Devil to an immovable object.60 It shares motifs with other stories like “Old Nick and the Dancing Girl,” and has inspired numerous stories and films where characters make deals with the devil.

Straparola and Basile

The fairy tale as a genre started to emerge in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Europe, specifically in Italy, with the publication of two foundational collections of folk and fairy tales. The first, The Pleasant Nights, was published in Venice in 1551 and 1553 by Giovanni Francesco Straparola; the second, The Tale of Tales, also known as The Pentamerone, was written in Neapolitan dialect by Giambattista Basile and published posthumously by his sister Adriana in 1634 and 1636.

These two works share many similarities. Following in the tradition of Chaucer and Boccaccio, both are structured around a frame narrative. In The Pleasant Nights, a group of exiled aristocrats, residing in a villa on the island of Murano, gather during the Venice Festival to tell stories over thirteen nights. Of the seventy-five stories in Straparola’s collection, fifteen have been identified as fairy tales, including early versions of “Puss in Boots” (“Constantino Fortunato”), “Iron Hans” (“Guerrino and the Wild Man”), and “Big Peter and Little Peter” (“The Priest Scarpacifico”).

Not only is The Tale of Tales comprised primarily of fairy tales — including early versions of “Rapunzel” (“Petrosinella”), “Sleeping Beauty” (“Sun, Moon, and Talia”), and “Cinderella” (“The Cat Cinderella”) — but its frame story is a fairy tale too. Princess Zoza, who is deeply melancholy, laughs one day at an old woman’s mishap. In anger, the old woman curses Zoza to only marry Prince Tadeo, who lies asleep in a faraway tomb under a fairy’s curse. The only way to break Tadeo’s curse is to fill a pitcher with tears. Zoza embarks on a journey to the prince’s tomb and fills the pitcher with two days’ worth of tears. However, just when a few more tears are needed, Zoza falls asleep, and a passing slave adds her own tears. Tadeo awakens, mistaking the slave for his savior, and marries her instead. Heartbroken, Zoza arrives at the prince’s castle, and using three magical gifts from fairies, curses the now-pregnant slave to crave for stories. At the slave’s command, Tadeo assembles the ten most talented storytellers in the city to entertain her. Over five days, each storyteller tells one story per day, resulting in fifty tales. Zoza tells the final story, using it as an opportunity to reveal the truth. Upon hearing it, Tadeo has the slave and her unborn child buried alive, and marries Zoza instead.

Both collections were written for a literate adult audience, and are thus filled with bawdy humour and vulgar content — a stark contrast to the more “sophisticated” and family-friendly Italian folk tales collected by the likes of Giuseppe Pitrè and Laura Gonzenbach in the nineteenth century. Basile’s stories, in particular, are filled with lurid and scatological elements: in “The Goose,” for example, a precursor to “The Golden Goose,” a magical goose excretes gold for two sisters, but when it is stolen by jealous neighbours, it only produces waste. The goose later attaches its beak to a prince’s behind, and only one of the sisters manages to free it, earning her the prince’s hand in marriage. Due to such earthy content and the obscure Neapolitan dialect of Basile’s work, these tales remain relatively unknown outside of literary circles.

Perrault and the Conteuses

In late seventeenth-century France, a trend emerged among the upper classes, particularly women, in which they would gather in fashionable “salons” and discuss matters of culture, art, and literature. These discussions sparked a growing interest in fairy tales, prompting the conteuses (female storytellers) to compose sophisticated, elaborate tales based on folk tale models.

As well as entertaining themselves, the conteuses used these stories to make subtle critiques of the corruptions and social injustices of the French court. Many of the conteuses’ stories, for example, commented on arranged marriages, reflecting their desire for the freedom to choose their own lovers. In d’Aulnoy’s “The White Cat” — which draws on motifs from tales like “The Frog Princess,” “Beauty and the Beast,” and “Rapunzel” — a princess, abducted by fairies, is forced to marry the king of dwarfs. She refuses, and when the fairies discover her plan to elope with her true love, a gallant prince, they feed him to a dragon and curse her to live as a white cat. The curse can only be broken if a prince who resembles her former lover in every way falls in love with her, which eventually happens.

The conteuses’ tales were first recited aloud in salons before being published in books. Among the most notable of these conteuses was Marie-Catherine d’Aulnoy, who coined the term “contes de fées” (“tales of the fairies”) because fairies were predominantly featured in her tales and many others’. Other notable names include Charlotte-Rose de la Force, Henriette-Julie de Murat, Catherine Bernard, and Marie-Jeanne L'Héritier.

The most famous and influential of these writers, however, was Charles Perrault, a civil servant in the court of King Louis XIV and a regular attendee of the conteuses’ gatherings. In the early 1690’s, Perrault published three verse tales: “Griselda,” “The Foolish Wishes,” and “Donkey Skin.” In 1697, Perrault published his collection Stories or Tales of Past Times with Morals, which contained eight stories, among them the well-known versions of “Cinderella” and “Puss in Boots.” As Iona and Peter Opie wrote:

“Perrault’s achievement was that he accepted the fairy tales at their own level. He recounted them without impatience, without mockery, and without feeling they required any aggrandizement, such as a frame-story, though he did end each tale with a rhymed moralité. If only it had occurred to him to state where he had obtained each tale, and when, and under what circumstances, he would today probably be revered as the father of folklore.”61

Perrault’s writing was simpler and more child-friendly than that of his female contemporaries, though it still retained a sophisticated, courtly charm. Curiously, his collection was initially published under the name of his then seventeen-year-old son, Pierre. While the exact reason for this remains unclear, some scholars, including Jack Zipes, speculate that Perrault wished to protect his reputation in the eyes of the French government.62 Also uncertain is whether Perrault was familiar with Straparola’s and Basile’s versions of his stories, though their plots were widely known even in his time. As the more elaborate, sophisticated (and somewhat convoluted) style of the conteuses’ stories fell out of favour, Perrault’s collection became a success and laid the foundation for future fairy tale anthologies.

Another noteworthy collection that sparked Western interest in non-European fairy tales was The Thousand and One Nights, also known as The Arabian Nights. The earliest known version, a fourteenth-century Syrian manuscript, contained stories from South Asia and the Middle East. However, the edition that had a profound influence in Europe was Antoine Galland’s French translation in the eighteenth century. Like many earlier collections, it featured a frame narrative: a king, believing all women to be unfaithful, marries a new bride each night and kills her the next morning to avoid betrayal. This cycle continues until Scheherazade, the vizier’s daughter, marries the king and tells him a story each night, cleverly delaying the story’s ending to ensure her survival. She maintains this pattern for 1.000 nights, ultimately softening the king's heart and saving not only herself but all future brides.

It’s important to note, however, that the most famous stories from The Thousand and One Nights — such as “Aladdin and the Magic Lamp” and “Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves” — were not part of the original manuscript. They were added in the French edition by Galland, who heard them from the Syrian storyteller Hanna Diyab. Additionally, some tales in the collection are early variants of European stories like “Cinderella,” “The Speaking Bird,” and “The Frog Princess.”63

Another famous eighteen-century fairy tale is “Beauty and the Beast.” Initially written as a novella by Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve, it was later popularised in an abridged, moralistic version by Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont.

The success of Perrault’s collection and Galland’s translation of The Thousand and One Nights sparked a growing interest in literary fairy tales in France. This movement culminated in Le Cabinet des Fées (The Fairies’ Cabinet, 1786-1789), a forty-one-volume anthology edited by Charles-Joseph de Mayer, which featured stories by many French authors, including those mentioned above. However, with the onset of the French Revolution, this trend waned in France, though it soon found a new life in Germany.

The Grimm Brothers

Except, at that time, what we now call Germany was then not a unified nation but a collection of around three hundred states, making them vulnerable to conquest during the Napoleonic Wars. This turmoil sparked debates among scholars about what it meant to be German, fueling a growing interest in collecting and preserving the folk traditions of the German past. Among those involved in this movement were the Romantic writers Clemens Brentano and Achim von Arnim, who published a collection of German folk songs and poetry titled The Boy’s Magic Horn.

But the most influential collection, the one that would shape the way fairy tales were to be written and recorded for generations, was compiled by brothers Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. Both studied law at the University of Marburg, where they were influenced by Professor Friedrich Carl von Savigny. Savigny believed that law naturally evolved from the language and history of a people, which sparked the Grimms’ interest in philology and, eventually, older German literature and folklore.

Wilhelm Grimm had previously contributed a handful of folk songs to the second and third volumes of The Boy’s Magic Horn, which led Brentano to ask the brothers to collect prose folk narratives for a potential project. He even sent them two tales written in a Pomeranian dialect — one of which was “The Fisherman and his Wife” — by the artist Philipp Otto Runge. The Grimm Brothers became deeply interested in the project and began gathering tales in earnest in 1806.

Some stories, like “Rapunzel” and “The Fisherman and his Wife,” came from literary sources, but most were collected orally from literate, middle-class friends, neighbours, and relatives, many of whom were women. A major contributor was Dortchen Wild, the daughter of a pharmacist, who later married Wilhelm. As noted by Nicholas Jubber in The Fairy Tellers, Wild’s own complicated relationship with her father may have influenced the troubling paternal figures in the stories she shared, like “Hansel and Gretel,” “Rumpelstiltskin,” “Thousandfurs,” and “The Six Swans.” Her strong work ethic and domestic knowledge also echo in tales such as “Mother Holle.”64

Another significant contributor was Dorothea Viehmann, a fruit-seller from Niederzwehren, who provided several tales, including “The Goose Girl.” Viehmann had an extraordinary talent for storytelling: not only did she bring the tales to life, but she repeated them with such precision that the brothers could transcribe her words verbatim. Despite her French ancestry, the Grimms held her in high esteem, seeing her as an ideal embodiment of the “authentic” German storyteller.

Other notable contributors included the Hassenpflug sisters — Marie, Jeanette, and Amalie — who told multiple versions of the same story, helping shape tales like “Little Red Cap.” Given their mother’s French ancestry, it is possible they were familiar with French variants of the stories they shared, including Charles Perrault’s “Little Red Riding Hood.” There was also Johann Friedrich Krause, a retired soldier who provided cheeky, amoral tales like “The Knapsack, the Sack, and the Horn” in exchange for old clothes.

In 1810, the Grimms sent Brentano a manuscript of fifty-six tales — known as the Ölenberg manuscript — as evidence of their progress. Brentano, by then, had lost interest in the project and ultimately misplaced the manuscript. Fortunately, the Grimms had made a copy of it, allowing them to continue with their work. The lost manuscript was later found in Brentano’s posthumous papers, thus providing scholars valuable insight into the Grimms’ editorial process. Despite his waning interest, Brentano continued to support the Grimms’ endeavour, while Arnim helped secure them a publisher.

In 1812, the first volume of the Grimm Brothers’ collection Children’s and Household Tales was published, which contained eighty-six stories. A second volume followed in 1815, adding seventy more stories, and bringing the total number of tales in the first edition to 156. Though the title might suggest an emphasis on children, the collection was originally intended for an adult, scholarly audience, as it contained extensive notes on the genealogy and variants of the stories.

The initial reception to the Grimms’ collection was mixed to positive. Some, like Brentano, criticised the tales as unpolished, while others, like Arnim, felt the academic presentation was ill-suited for children. Some parents objected to the stories’ violent and superstitious content, deeming the collection inappropriate for young readers. Nevertheless, many others began reading the tales to their children — and to themselves. Despite the criticism, the first edition sold well enough to warrant a second edition in 1819.

Over time, the collection went through six further editions — with Jacob doing most of the research and Wilhelm doing most of the editorial work — till the seventh and final edition in 1857. During this process, some tales from the first edition were omitted in subsequent editions. The reasons varied: some, like “How Some Children Played at Slaughtering,” were considered too brutal for the collection’s increasingly young audience; others, like “The Mother-In-Law” were incomplete or fragmentary. In fact, the first edition included a group of stories simply titled “Fragments.”